Before Christmas, I had the pleasure of spending a night at the Mabel Dodge Luhan House in Taos, New Mexico, and have written about it for Southwest Contemporary. Luhan was a writer and wealthy patron of the arts from upstate New York. She moved to Taos at the beginning of the 20th century, divorcing her third husband, who had lured her there, and marrying her fourth and final husband, Tony Lujan, from Taos Pueblo. Mabel and Tony spent the rest of their lives together in the “Big House,” the sprawling adobe structure they erected, which now exists as a three-star hotel and resort.

You can find the article here.

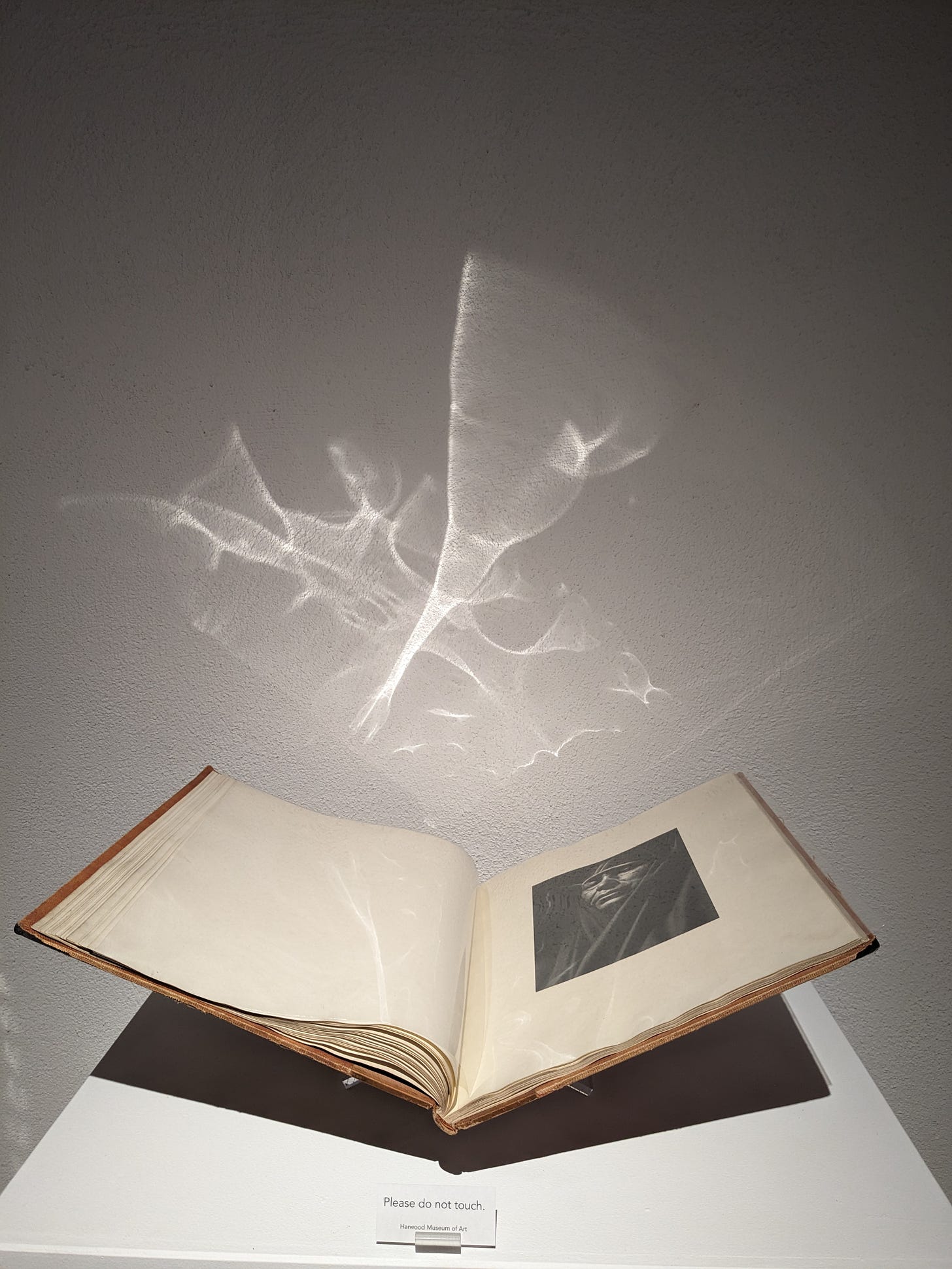

The article won’t tell you that I saw Santa Claus and Kit Carson serving hot cider outside of the Kit Carson Museum on Kit Carson Road. It also doesn’t mention that I was taking a photography class and was running around taking bad pictures with a rented DSLR Canon, including of the bighorn sheep crossing the hiking trails near the Rio Grande Gorge Bridge, which my grandfather helped engineer during his long stint working for the New Mexico highway department. I also made my partner pose among the white paint on white canvas in the white cube gallery space at the Harwood Museum, where the abstract expressionist work of Agnes Martin is on permanent display.

Before retiring to the Nicolai Fechin room at the Luhan House, I went to a “Meet the Donkey” party in Talpa, a sort of artist-cowboy debutante ball for a Jerusalem donkey named Minister. Its owner uses Minister as a source of transportation, riding him down the busy Paseo Del Pueblo Sur to Smith’s grocery store.

I also ran into old friends from Taos and met new ones, including a Palestinian woman from New York who finds herself in rural New Mexico learning about historical and enduring community irrigation systems—the same kind you see at the Georgia O’Keefe House in Abiquiu. This system fed her flourishing secret garden, which the Georgia O’Keefe Museum in Santa Fe maintains, fully restored to its former glory.

There’s something to say about this Palestinian woman working on community water irrigation in relation to the water scarcity and the mass forced starvation of Palestinians in Gaza. But I’ll leave those dots hanging in the air for you to connect.

The next morning, at a long banquet table in the dining room of the Luhan House, I met an elderly woman who identified herself as a writer, proudly beaming that she was staying in Mabel’s room. Outlining her latest manuscript, a historical account of a 19th-century Virginian woman’s integration into the Swanee tribe, I nodded my head, affirming the fitness of her pursuits in relation to her affinity for Mabel.

Reluctantly, I admitted to her that I write as well. Instead of asking me what I write, however, she asked me about what I was reading. When I told her Second Place (2021) by Rachel Cusk, she raised her eyebrows in non-recognition.

“It’s loosely based on Mabel and her memoir, Lorenzo In Taos–about D.H. Lawrence’s visit to this house in 1922,” I clarified.

In her New Yorker review of Second Place, Rebecca Panovka rightfully criticizes Cusk’s simplified version of Lorenzo in Taos, which renders Tony an adopted child of uncertain ethnicity. By deracinating Tony, Cusk glosses over the complicated relationship Mabel and he shared. Mulling over the sudden rise of interest in a divisive figure like Luhan after the 2021 publications of Cusk’s novel and a new biography of D.H. Lawrence, Panovka bitingly concludes: “Not every forgotten woman is in need of a bio-pic.”

Yet, when I visit Taos, immersing myself in its dramatic landscape, I find myself in a position similar to Luhan’s, wanting to establish roots here and build a creatively fulfilling life. While watching the sunsets over the mountains and hearing the grass rustle over uninterrupted prairies of undeveloped, Pueblo-protected land, no amount of rationality and education in social politics helps me see this place as anything but mystical and available to me, too.

Returning to Taos always feels like returning home, and this desire to belong to a community that continues to grow and gentrify and push my artist friends to the brink of their ability to survive there makes me feel guilty. In my article, I write about this guilt, connected to the history of Western expansion and exploitative modernist art-making in the region.

However, in this piece, I also neglect to inform you that I lived in Taos from August 2017 to August 2018. Fleeing the East Coast, and, although I didn’t realize it at the time, also a long-term relationship and my life in academia, I joined my best friend, Damien Moreau, in Valdez on the outskirts of Taos, where he had secured a house to rent on a cliff in Gallina Canyon right next to the D.H. Lawrence Ranch.

I’ve often referred to this year as a life highlight and consider Taos one of my favorite places to live. It’s complicated and bittersweet to admit as much, though. Damien was in a steep slide down into a depressive state that he couldn’t overcome. I watched his character radically change under the murderous magenta sunsets over a mesa dusted with minty sagebrush. In December 2019, he succumbed to his stubborn death wish. I’ve written a lot about his suicide in a secret blog that is formed as a series of missives to him. Maybe I gave you access, and you have read it. At any rate, Taos can never fully be home for me again because it no longer exists on the same dimensional plane as Damien.

Although I ceased writing to Damien directly, I still think of topics for these letters to him. I’ve, of course, been angry at him and dismissive of his sincere desire to leave this planet, thinking that he was stronger and could have endured it better than he thought. But with the pandemic, rise of authoritarianism, burning of the planet due to climate change, increased legal protections for narcissistic, comic-book-villain billionaires, and genocide in Gaza, I’m not so sure.

This was not the introduction I intended to write for this article! But it is the one I have written. Although it has little to do with my essay’s contents, it feels right.

Please find a very different exploration of Taos and its history in Southwest Contemporary here.

You can also find a list of my other publications here.

And, if you haven’t subscribed to my Substack yet, please do so here.

Leave a Reply