I. Eager to Offend

In February 2023, I went to the Chez Artiste, my favorite independent film theater on South Colorado Boulevard in Denver. “One for Corsage,” I told the elderly woman at the register. Theater number one was almost finished with the previous screening, so I paced around the lobby, looking at the DIY staff poster board displays about current features. Pinned to the poster board with the heading, TÁR, were two reviews: A.O. Scott’s take for The New York Times and Marin Alsop’s comments in The Los Angeles Times.

Alsop’s name rang a bell because she conducted the Colorado Symphony. Also, a year earlier at the Chez Artiste, the theater showed The Conductor, a documentary highlighting the grounds Alsop broke as a female conductor. Recognizing a reference to herself in the titular character of Todd Field’s Tár, played by Cate Blanchett, Alsop stated, “I was offended: I was offended as a woman, I was offended as a conductor, I was offended as a lesbian.” My eyes moved from Alsop’s statements to a picture of Blanchett standing imperiously in a stiff white collar, baton in hand, and I decided I was offended too.

Later, after the film awards ceremonies, a friend asked me if I had watched Tár. I told her I had little interest in seeing a woman behave like Shakespeare’s Richard III to impress old, white-man colleagues. “The reviews are mostly bad and wrong,” she replied. Trusting her instincts, I finally rented Tár (and told her to watch Corsage).

For the first half of the film, I held my pre-judgments. The long opening credits (playing Tár’s recording of a Shipibo-Conibo singer during her ethnographic work in Peru) surely signaled the start of a long, self-congratulating art film. Indeed, I read several reviews aligning Field with cinematic geniuses Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky. While deserving of these comparisons, Tár’s fast-paced dialogue and images differ significantly from Kubrick and Tarkovsky’s slow-paced, quiet scenes. Tár bombards its audience with a barrage of words and images at such a rate that superficially analyzing the film requires frequent hits on the pause button.

I held my guard up as the film moved into the much-discussed masterclass-at-Julliard scene. In this scene, Tár reprehends a self-identified pangender, BIPOC student, Max, who insists that the dead, classical European music canon is just not his “thing” (same, Max, same). Tár is crass at Julliard. She smirks at Max’s responses to her questions. When she asks Max why they chose to attend Julliard, they flatly respond that it is the nation’s best music school. Retorting that Julliard is “a brand,” Tár digs for Max’s deeper compulsions, so Max discloses an admiration for former Juilliard graduate and violinist Sarah Chang. While Tár wants to uncover Max’s passion for music and conducting, a fair interest for a mentor, she finds Max cliché and so suffocates their responses with her own effusions about the music she prefers, also notably cliché.

Alsop sprang to my mind again when Tár, seated next to Max on a piano bench, violently clamped down on Max’s nervously shaking leg and said, “Don’t be so eager to be offended. The narcissism of small differences leads to the most boring conformity.” Aware of her own provocativeness, Tár decidedly scoffs at the contemporary piece Max chooses to conduct by Icelandic composer Anna Thovaldsdottir (remarking how the strings “behave as if they’re tuning” and the composer’s directions “sound like René Redzepi’s recipe for reindeer”). Thus, as Tár targets Max, the film targets its audience and all of the real-life musicians, composers, and conductors it name-drops, letting us know that it aims to offend everybody.

The film aims at its audience from the first scene, featuring New Yorker writer, Adam Gopnik, playing himself and fawning over Tár’s illustrious resume for a packed stadium of chittering admirers. Gopnik lends unwavering realism to the scene, creating the strong impression he’s leading a recent interview with a real, renowned person we know embarrassingly little about ( the opening introduces us to Tár, making us instant experts–a jury poised for a guilty verdict). This initial scene also serves as a masque or an allegorical performance of a highly educated, liberal audience’s relationship to Tár’s soon-to-be-controversial celebrity, holding a mirror up to us as we watch.

This mirror is the first of many, both literal and figurative, in Tár. Offering a reflection of a reflection of a reflection . . . Tár creates an infinity mirror effect visually and in its textual content. As I argue, the many reflections or repetitions of words and images throughout the film highlight Tár’s postmodern anxiety regarding pastiche, or, the fear that everything one creates, including one’s self, is a copy of something else. Indeed, Tár and Field, as the film’s maestro, possess this fear as much as Tár the character.

These self-referential codes in the film run both backward and forward, like a palindrome, of which Tár includes several (as included in the title of this essay, accompanied by an additional anagram for Tár: “art”). Such palindromic play references Kubrick (think, “redrum” from The Shining), who Field worked with, ostensibly aligning Tár’s concern about mimicking her mentors with Field’s similar concern. The temporality of the film too, moving backward and forward between past and present, presents an increasingly frenzied chiasmus that offensively overwhelms us with meaning while withholding any certifiable truths.

II. Hear and Now

Emphasizing its interest in the “now,” Tár begins en medias res with the Gopnik interview, alluding to our post-COVID, #metoo, “cancel culture” moment–a myriad of current, hot-topic phenomena that eagerly offend us. The film also introduces us to such cultural tensions by playing with the words “kayvanah” and “Kavanaugh.” Discussing her mentor, conductor Leonard Bernstein (who, in real life, mentored Alsop), Tár establishes his use of “kayvanah, [the] Hebrew word for attention to meaning or intent.” Gopnik comments that the audience might mishear this unfamiliar word with the more familiar “Kavanaugh,” as in Brett Kavanaugh, the associate justice in the Supreme Court who Christine Blasey Ford accused of sexual assault.

Ignoring Gopnik’s observation, Tár expounds on her mentor’s idea with the rhetorical question, “What are the composer’s priorities and what are yours, and how do they complement one another?” Thinking about this Tár-Bernstein emphasis on interpretation, the film also conducts how we navigate these current headlines and implicitly asks us to consider its priorities as opposed to ours.

By the end of my first viewing of the film, I immediately rewatched it to discover and contemplate the many homonymic mishearings and other word plays in the film. Additionally, after rerunning the film, I noticed that hearing “Kavanaugh” as an invitation to take offense (to dismiss Tár because of the parallels between her and others marked by “toxic masculinity”) blocked my ability to unpack anything more profound in the film. Put differently, if we hear an invitation to offense, we miss the film’s absent ideological allegiances.

The film asks us to sit uncomfortably with urgent cultural issues, denying us the reward of validation from seeing our beliefs (on the right side of a political debate) played back to us. The film thereby alerts us to our problematic expectation for such validation. It also critiques the politically bipartisan U.S. for manufacturing an illusory black-and-white world in which a right and wrong side exist for everything, including artistic representation. In this way, the film forces us to hear both kayvanh and Kavanaugh, drawing a connection between the debates shaping our current perspectives and the Tár-Bernstein question rephrased as: What are the film’s priorities and what are yours, and how do they complement one another?

III. Watch, Repeat

The film’s implicit request to watch and rewatch it contributes to its head-scrambling infinity mirror effect. For instance, the Julliard scene replays itself later in the film as a heavily-edited video uploaded to social media. This video pulls out the most memorable details from the situation, proving that our memory also works to take Tár’s abrasiveness out of context.

The social media upload begins with Tár stating, “You must be a Negro product exploited by the Jews,” while showing Tár swinging a punch at Max’s head. This violent gesture recurs when Tár says, “Now, you could masturbate, but what are you actually doing to me?” as she clamps down on Max’s leg. When I watched the first Julliard scene, in the “real-time” of the film, the “punctums,” or emotionally striking moments, included these very gestures and words that, re-edited to create a parallel narrative, highlight something truthful about the violence enacted by Tár.1I misuse Roland Barthes critical term. “Punctum,” as Barthes uses it, denotes the “prick” a certain image delivers to viewers who have an intensely private, emotional response to what they view. In fact, Tár experiences a form of “punctum” in the emotional response she has to music, which she tries to translate to others. In my use of punctum, the emotional responses I had to the Julliard scene were more social than individual as I imagined myself being offended on grounds of sex, race and gender that are all socially informed. Speaking of Barthes, this very essay references him and his book S/Z, in which he succumbs to his desire to analyze every word from a short piece of fiction. Similarly, I offer a lengthy reflection of Tár out of the desire to analyze every minute of it.

Illuminating how my memory worked to re-imagine the initial scene, I failed to connect Tár’s opening line with Edgar Varése. After Max expresses admiration for Varése, Tár quotes Varése’s impression of jazz music to gloat over Max’s ignorance and hypocrisy. While I remembered all of Tár’s lines re-presented in the video, I failed to recollect the full circumstances because, although her speech is staggeringly composed, her fast pace and academic content purposefully lost me. And so, the re-formatting of the Julliard scene struck me as only mildly tampered with since I remembered condemning Tár’s behavior in the original circumstance but couldn’t recall the full context.

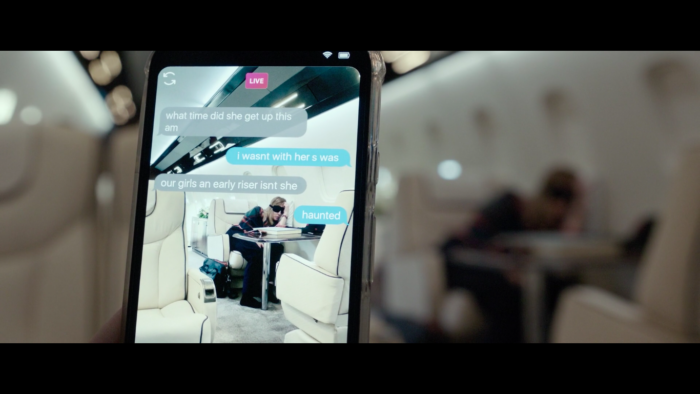

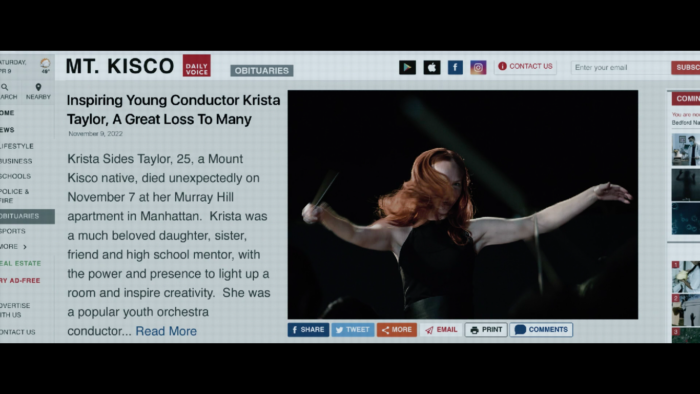

During her interrogation by the Berlin Philharmonic Board about the video, Tár defends herself by stating, “[the video] create[s] linguistic traps to completely redefine my words . . . There’s no way that was done in real time.” This statement reminds us that the film, too, creates linguistic traps and intentionally edits scenes to control our experience of filmic temporality. Considering temporality, the film suggests a ghost story from the initial shot. Showing the phone screen of an unidentified person filming Tár asleep on a private jet, one person texts, “Our girls an early riser inst she [sic].” To which the other responds, “haunted.” Indeed, Tár cannot shake the phantom of her former, mistreated protegee (and possible lover), Krista, who kills herself early on in the film. As a reflection of Tár’s haunted psychological experience, the film continually repeats and recontextualizes the past.

While we never see Krista’s face, we become familiar with her shoulder-length copper hair as her specter sporadically flashes on the screen. Furthermore, Tár repeatedly fails to erase Krista’s phantasmic trace from her life. Early in the film, she notably and weakly attempts to clear her inbox of any correspondence with or about Krista (she also takes her assistant’s, Francesca’s, laptop to do the same). Of course, Tár spotlights her guilt by confirming her abusiveness through several emails she writes. These emails discourage various orchestras from sponsoring Krista as an Accordion scholar (Tár’s organization that mentors female conductors and pairs them with esteemed orchestras).

This vengeful spirit shows up in Tár’s dreams and returns in Tár’s waking life as a lawsuit backed by her grieving parents (removing Tár from the board of Accordion). Through this mechanism of the ghost story, the film signals the past, which remains only partially revealed to us. Moreover, “accordion” (an instrument Tár is pictured playing in childhood and seen playing in a memorable scene when she aggravates her neighbors) relates to the film’s treatment of time, which moves in and out like an accordion.

IV. As In The Beginning, So In The End 2 This phrase is an antimetabole, not a chiasmus.

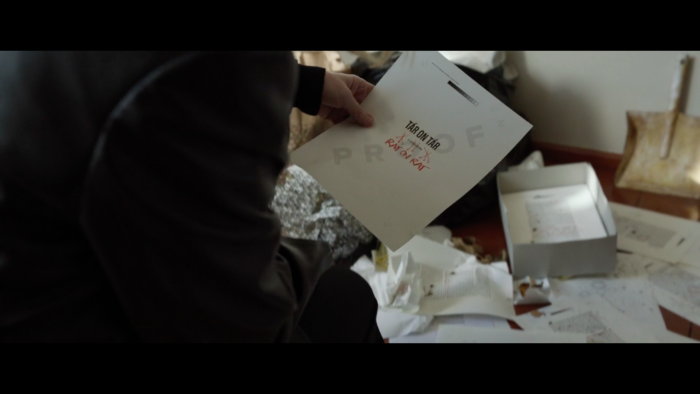

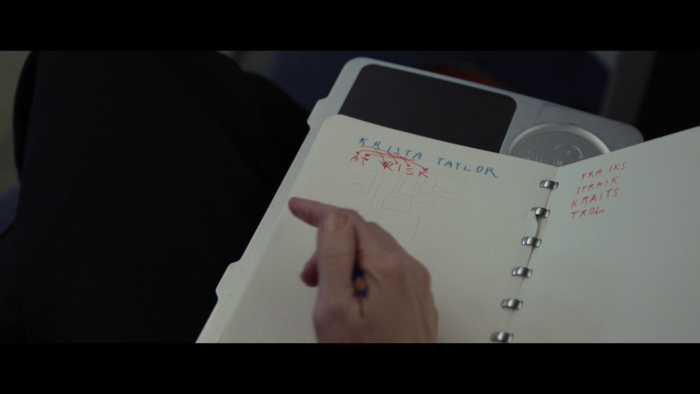

The film’s obsession with chiasmus (a rhetorical device that states things in the reverse of its original order) comes across through Krista’s ghost (forcing us to revisit Tár’s past) and ubiquitous palindromes. After quitting her position when Tár fails to advance her conducting career, Francesca leaves behind a copy of Tár’s manuscript in the apartment she hurriedly vacates. Tár finds the manuscript with the title, Tár on Tár, crossed out and Rat on Rat written in its place, pointing out the fitting palindrome of Tár’s name (a name that Tár invents as we learn when Tár returns to her New England childhood home littered with certificates and awards for “Linda Tarr”). Additionally, Krista writes an email to Francesca with the subject heading: Tárget. Tár herself, on a plane from New York to Berlin, writes “AT RISK” underneath Krista’s name in her notebook, an anagram, before crossing it out.

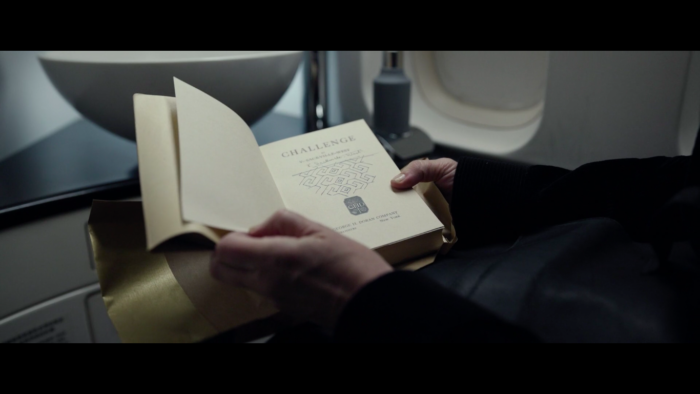

Before writing “AT RISK,” we find Tár in the bathroom, unwrapping a gift from Krista, Vita Sackville-West’s novel, The Challenge (Sackville-West was an early 20th-century modernist, lesbian writer who famously had an affair with Virginia Woolf). This novel revolves around two women who, as they vacation together one summer, decide to spend their lives together. Ultimately, though, they return to their respective homes and husbands. Pausing this scene as Tár turns to the book’s title page, you’ll find it decorated with a design widely used by the Shipibo-Conibo. Later in the film, when Francesca tearfully informs Tár of Krista’s suicide, we discover that Tár, Krista, and Francesca spent a summer together on the Ucayali River (in the Peruvian region of the Shipibo-Conibo).3Significantly, Francesca, who usually wears her hair in neat updos, wears her hair down in the same style and cut as Krista in this scene. In this way, a chain of palindromes and textual allusions presents the mysterious love triangle between these women.

Chiasmus is also visually codified in the many mirrors and reflections we see in the film. At the film’s end, Tár peruses her scorebook in a vacant dressing room in the Philippines (where she is exiled after her dismissal from the Berlin Philharmonic) before her final conducting performance in the film. She sits facing a mirror that creates an infinity effect, and after receiving her stage call, she walks through a hallway marked by similar, repeating door frames. She stands backstage breathing nervously, just as she did at the film’s beginning, before appearing in front of the audience for her New Yorker talk.

When the end credits roll as the theme to the video game Monster Hunter erupts from the orchestra and the camera pans out to a cosplay audience, the end credits provide a framing device with the opening credits. However, instead of singing from a Shipibo-Conibo person, music from Monster Hunter plays followed by a dub-step production (both of which, of course, are jarringly out-of-step with the rest of the film’s soundtrack). Ending as it begins in terms of style, the film presents itself in an infinite loop, with Tár’s fall to the “lowbrow” linking back to the pinnacle of her career. What’s more, in a display of poetic justice, Tár conducts a children’s orchestra–Krista also conducted a children’s orchestra (as we learn from a brief glimpse of Krista’s obituary).

V. Psychological, Ethnocentric Horror

If you watch the film’s beginning after it ends, the opening’s disjointed flashbacks, now contextualized with the rest of the narrative, become available for analysis. On a second view, for instance, we might better guess the identities of the mysterious people derisively texting about Tár as one films her asleep under an eye mask. Assumedly, Tár is on her way to New York for her interview on the private jet that benefactor Eliot Kaplan loans to her (as long as she bolsters his own conducting ambitions). After this conversation, one texter suggests that the unconscious Tár “has a conscience,” and the other responds, “you still love her then.”

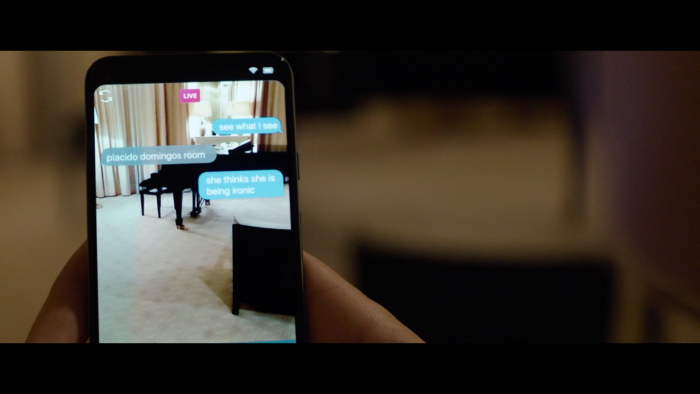

Considering the evidence, Francesca must be filming Tár as she texts with someone else, perhaps Krista? Indeed, during the interview, we glimpse the back of Krista’s head among the audience. Furthermore, after the interview, we see another live video phone chat where the person holding the phone shows how Tár rented renowned Spanish opera singer Plácido Domingo’s room for herself. One of them comments, “she thinks she is being iconic.”

Yet, when we last see these two people texting in the film, at Tár’s book launch, Francesca and Krista are gone from her life. In this scene, Olga, the new cellist in the Berlin Philharmonic (or, Tár’s “fresh meat,” as one Twitter commenter in the film observes), accompanies Tár on her trip. Before the camera cuts to the anonymous person’s phone screen, Tár jealously watches Olga flirting with a young man in the back of the room, typing something on her phone before sharing her screen with him. Therefore, Olga, like Francesca and Krista, is an unlikely culprit for directing the video chat as we see her distracted, uninterested, and in a different part of the audience than the mysterious texter.

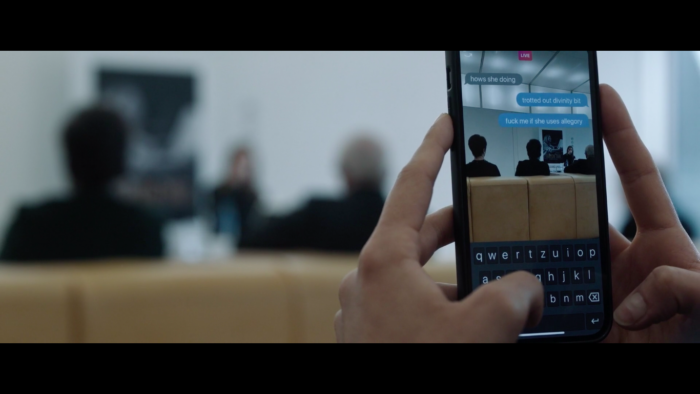

Several critics have reviewed this film as a psychological horror in which, as the film progresses, it becomes increasingly difficult to separate what happens in Tár’s head from what happens in objective reality. Considering this reading, Tár’s paranoia and inner critic feasibly compose these messages. Therefore, as Tár imagines watching herself at her own book reading, observing Olga’s apathy and fearing a similar failure to reach the rest of her audience, she critiques herself, jeering, “fuck me if she uses allegory” (as one texter comments, reflecting Tár’s own brutal inner editor). When we first see Tár in the film, blinded and asleep, we may also interpret this moment as a dream or hallucination, in which Tár, feeling vulnerable (as someone blindfolded before being shot–which she is, by a camera), imagines being filmed and maligned by others.

Further considering Tár as a psychological horror, the dream sequences in the film unveil Tár’s inner world or the conscience she may or may not have. These sequences appear from behind a lens immersed in water as if Tár watches from inside an aquarium. This aquarium effect recalls Tár’s visit to the “fishbowl.” At the film’s end, Tár visits a massage parlor in the Philippines, where the receptionist directs her to “the fishbowl”–a room with sex workers in numbered robes. Number five boldly locks eyes with Tár, seeming to choose her. The number five signals both Mahler’s Fifth Symphony (the piece Tár conducts for the Berlin Philharmonic before her dismissal) and the letter “S,” for Sharon, Tár’s wife, sometimes referred to as “S.” As Tár interprets Mahler’s Fifth as a symphony about love and marriage, the invocation of these ideas at this moment horrifyingly underlines their nonappearance. Instead, a new ghost from the past, beyond Krista, appears to haunt Tár.

Tár’s lovers inhabit Tár’s shadowy dreamscape. In one dream, Krista holds Tár in a violent embrace. After Francesca leaves Tár, Tár dreams that Francesca whispers to Sharon and Olga as they stare at her. This whispering reminds us of Tár mentioning to Sharon her fear of “Chinese whispers,” a sinophobic phrase alluding to the incomprehensible sound of Mandarin or Cantonese to anglophones. Literally, “Chinese whisper” means a “game of telephone,” in which an original statement gets increasingly distorted through numerous retellings. In the background of this dream, a man from the Shipibo-Conibo (who Tár has framed in a picture in the Berlin apartment she keeps separately from her family and who renames a nameless idol) silently presides in the background.

These dreams highlight the colonial trope of using non-western cultures as stand-ins for otherworldly or spiritual out-of-timeliness and augment the film’s horror. The colonial horror of the film directly refers to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (and sadistic, imperialist Kurtz’s final proclamation, “the horror, the horror”) since, at the end of the film, Tár ends up in the Philippines where Francis Ford Coppola shot Apocalypse Now, based on Conrad’s novel.

For most of the film, Tár uses Peru to invoke the “horror” of the past. After we hear a member of the Shipibo-Conibo people singing in the opening credits, we learn, in Tár’s discussion with Gopnik, that the Shipibo-Conibo only sing when they are on “the spirit side,” connected to an alternate realm inhabited by their ancestors. Indeed, before Tár composes her piano piece in her Berlin apartment (the apartment with the photograph of the Shipibo-Conibo man from her dreams hovering over her, obscured by smoke–a symbol of the communicative pathway between earth and heaven), she ritualistically lights two candelabras on either side of a mirror, presumably calling “the spirit.”

This ritual also works to conjure Krista, who, after Tár’s first enactment of this ritual, appears in the distance, in another room, as Tár fetches a scroll to mark her notations. Additionally, in this scene, Tár’s work is interrupted for the first time by the alarm of her dying neighbor’s medical device, a harbinger of death. In this way, Tár flattens Shipibo-Conibo culture to lend spirituality and another ghostly layer of experience to Tár’s world.4We could also think about how Kubrick, in The Shining, uses the “magical negro” trope with the inclusion of a black clairvoyant as well as in the film’s allusions to the brutal past of Western expansion resulting in the confiscation of Native land and the murder of many Native Americans. In this way, Tár again presents itself as Kubrickian pastiche.

Tár’s exile to the Philippines at the film’s end also magnifies Tár’s demotion to the dilapidated “third world,” visibly devoid of “high” Western culture and art. As the film hops around different countries, it also reveals the many temporarily-inhabited homes of Tár: the sterile high-end Plácido Domingo room equipped with a grand piano in New York, the unwelcoming brutalist Berlin apartment Tár shares with her family, the separate studio she invokes the spirit from and composes her music in (she also courted Sharon while living in this apartment; later, she courts Olga who practices her cello solo there), and her final room in the Philippines that, as she pulls open the curtain over the windows, reveals a panorama of a city not often referenced in western film (and so unknown and incomprehensible, like a “Chinese whisper”).

Unlike Peru, which represents the past and the otherworldly, the Philippines represent dystopic futurity (“Asian-ifying” the future as iconic science fiction films such as Blade Runner do). The idea of “dystopia” is also cited when Cirio, one of Tár’s guides, dissuades her from swimming in a river left crocodile-infested after “a Marlon Brando movie” (Apocalypse Now) was filmed there in the 1970s. Through this direct reference, the film acknowledges its postcolonial bungling and, once again, invites our offense.

VI. Postmodern Robots

As Max storms out of the Julliard classroom, Tár calls them a “robot,” her favorite insult, which she uses multiple times throughout the film. Indeed, “robot” is uttered so frequently that it becomes a robotic cliche, invoked by the film as if to say that finding offense to its content proves that you, too, are a mindless slave to vapid, millennial social scripts. It also points to Tár’s Freudian overcompensation–she repeatedly exhorts that others are robots to deflect her fear of exposing herself as one. Neither Tár nor we escape this cultural critique and the phenomenological possibility that we are all made robots by our shared social-political context. In this way, we have no choice but to fall in line with what our moment in history demands because our identities, pleasures, interests, and abhorrences are all pre-established and inherited.

The film’s anxious preoccupation with postmodernism, in which everything said or created reveals itself as a copy of something else, illuminates this fear of being seen as a robot, unable to exceed its programming and invent something new. During a lunch with her predecessor, Andris Davis, Tár talks about writing her book, Tár on Tár. She tells Andris that she is “stuck in pastiche,” and Andris responds, of course, ”[W]e all have the same musical grammar.” Andris then proves that Beethoven plagiarized Mozart, depressing Tár, who wants to liberate herself from mimesis or imitative art.

Tár wants to create something unique but fears that she is just another repetition of her predecessors, particularly Leonard Bernstein, who she constantly quotes. Bernstein believes the conductor interprets the past for the audience and, in this way, as modernist icon Ezra Pound insisted, “make[s] it new.” Drawing this parallel to Pound, I suggest that since the early 20th century, art and culture grew self-aware of the predominance and inescapability of pastiche.

In the Julliard scene, Tár rephrases Bernstein’s idea when she proclaims, “Now is the time to conduct . . . music that everybody knows but will hear differently when you interpret it for them.” Tár wants to bypass the dilemma of repetition without end by privileging the genius of interpretation and elevating the status of the interpreter (conductor) over that of the creator (composer). Otherwise, one becomes a “robot” capable of appreciating human culture without contributing to it. In her passionate decry, though, she repeats Bernstein’s ideas, exposing the unoriginality of her very passion. Thus, as she criticizes Max for lacking similar fervor she reveals her own struggle to access a motivation or an idea that doesn’t already come from something or someone else.

Additionally, for Bernstein and Tár, the conductor liberates the audience from a language-based experience of consciousness and the world through the conductor’s interpretation of emotion. Emotion transcends language by communicating a deeply felt understanding without words, thereby evading cliches and scripted language. During her interview with Gopnik, Tár discusses her preparations to conduct Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as the head conductor of Berlin’s Philharmonic (the only one of Mahler’s nine symphonies unrecorded by her, showing Tár in the middle of a linear trajectory or en medias res where the film itself begins). She further explains to Gopnik that she interprets this piece as an expression of “love” since Mahler composed it soon after marrying his wife, Alma (who, Tár notes, later betrayed him for another man). Therefore, love allows Tár to present this symphony in a way not heard before.

VII. If I Only Had A Heart

The film juxtaposes Tár’s interest in accessing and translating emotion and love in music to her cold “transactions” with the people in her life (as Sharon, during an argument with Tár, observes that most of Tár’s relationships are “transactional”). In fact, instead of emotion, Tár finds marriage bound by “rules.” This idea arises when Tár and Francesca drive to the airport after Tár’s interview with Gopnik. Implored by Tár to speak honestly about her interview, Francesca admits to disliking Tár’s discussion of Mahler’s marriage to Alma, noting that Tár exaggerated Alma’s betrayal. Francesca reminds Tár that Alma was a conductor, but Mahler insisted (and here they quote the apocrypha together), “There isn’t enough room for two assholes in the house.” Tár goes on to lecture Francesca that Alma understood her position, saying, “She agreed to those rules . . . #RulesOfTheGame.” Although the specific “rules” she refers to remain unclear.

For Tár, while one chooses to ventriloquize social scripts from social media (like a robot), one necessarily abides by social contracts, such as marriage. Notably, Tár ironically invokes the language of the “robot,” which follows the rules instead of making them, when she uses a hashtag to make her point. Tár’s slippage reveals a disavowal of the idea that everyone implicitly consents to the #RulesOfTheGame and thus their unfreedom.

Additionally, this conversation takes place in transit through a tunnel. In fact, several scenes are shot in tunnels suggesting the film’s “tunnel vision,” or how it blocks our peripheral vision, precluding an understanding of the whole picture. In this tunnel scene, the “rules” prevent Tár’s view of a complete understanding of love and marriage. The general “tunnel vision” of the film includes the limited outlook we get from within Tár’s psyche, seeing everything from her eyes, which limits an understanding of the ideas and parts of her life she renounces.

These unclear and implicit rules of marriage come up again in the Julliard scene when Max and Tár debate Bach by considering if his “prodigious performance in the marriage bed” impacts the value and quality of his music. While Max’s disdain for Bach’s sexual behavior makes those of us unfamiliar with his biography wonder how many illegitimate children Bach begat, Bach, in fact, had ten children (surviving into adulthood) from two separate marriages. Bach’s sizable brood only underlines his active sex life with his spouses (ugh, breeders!).

Tár, of course, has one adopted child, Petra, and no reproductive evidence of the in/activity of her own sex life. Put crudely, the rumors about her promiscuity lack the evidence of bastards. Interestingly, as Tár contemplates Max’s dislike for Bach, she boasts that she, as a “Uhaul lesbian,” cannot commend Beethoven’s biography. In this way, Tár proves to Max that she also occupies a queer subjectivity and knows the modern slang accompanying it. Yet, “Uhaul lesbian,” referring to the serial monogamy of lesbians who, after briefly knowing a partner, move in with that partner, doesn’t fit what we observe about Tár–or shouldn’t because she is married.

When it comes to the “rules” of marriage and being an admirable spouse, Tár lies and has alleged affairs with younger women. In the scene where we first meet Sharon, we learn about her heart condition. Sharon’s heart, as a metonym for love, illuminates a marriage problem. Tár, arriving home from New York after her Gopnik interview, finds Sharon frantic because she cannot find her metoprolol. Indeed, she cannot find it because Tár pilfers these pills to use for herself (we see her first taking one to calm her nerves before she goes on stage to meet Gopnik). In other words, Tár controls Sharon’s heart and deliberately deprives it of what it needs to function properly.

Pretending to find a “loose pill” in a drawer, Tár gives Sharon her medication and puts on a song to lower her heart rate. Over the instrumental music, Tár sings, “I’m feelin’ a feelin’ for something there ain’t too much of.” Again, the “feelin’” of this marriage is lacking, and as Tár goes through the motions of spousal care and affection, the content of the song she sings underlines its absence.

Later in the film, after Sharon learns of Tár’s expulsion as the head of Accordion, Sharon again refers to the “rules.” During this argument, Tár presumes Sharon is upset by the rumors of Tár’s various affairs with young women, which Sharon surprisingly deems “forgivable.” Instead, the rules Sharon expects Tár to follow include reporting any threat to their family. In the absence of love, the rules, or the contract, matter most. Sharon also concludes the argument by stating that Tár’s relationship with Petra is Tár’s only “non-transactional” relationship. By stating this, Sharon lets Tár know that she always understood their relationship to be transactional–she understood the rules of marrying an “asshole” conductor and never expected complete love and devotion.

VIII. The Misogamist-Misogynist

Tár’s focus on the archive of love and marriage regarding classical music composers illuminates her unrealized emotional and domestic fantasies. Moreover, in an ironic moment between Tár and her assistant conductor, Sebastien (who Tár wants to have replaced), we learn the word for a person who hates marriage–misogamy. When Tár enters Sebastien’s office to dismiss him, the discussion turns into a volley of insults in which Sebastien accuses Tár of eliciting sex from her protegees in exchange for professional advancement. Tár calls Sebastien a “misogamist, which he hears as “misogynist.”

Tár clarifies that his hatred for marriage comes across in his pursuit of Aldris, an already married man. This mishearing, in line with the other homophones in Tár (including kayvanah and Kavanaugh), emphasizes the significance of both words. In this case, these designations apply to Tár. Additionally, both terms are at play in destroying marriage by emphasizing fear over love.

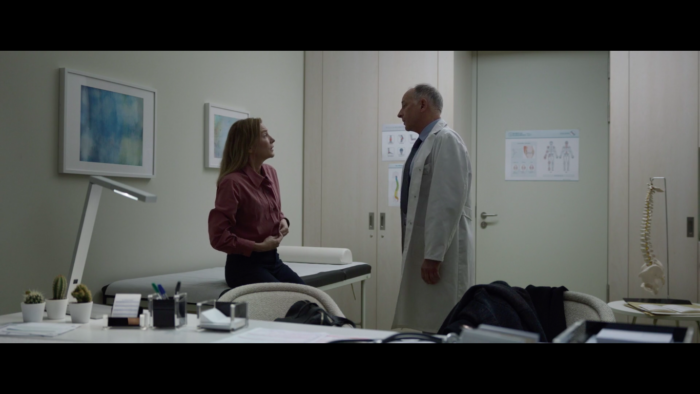

In another instance of homophonic slippage, Tár sees a doctor in Berlin who examines nerve damage she acquires under mysterious circumstances. Hearing the doctor diagnose her with “nostalgia,” the doctor corrects her, restating, “notalgia, without a ‘s.’” No “s” signifies Sharon, referred to as “S,” and implies Tár’s dearth of happy associations with the part of her past shared with Sharon. Nostalgia without a “Sharon” thereby refers to Krista, the primary ghost haunting Tár.

Tár thus diagnoses herself with painful nostalgia, which denotes nostos (return) and algos (pain) in the Greek roots of the word. When Tár tells the doctor that the notalgia feels akin to a sunburn, she refers to both the pain of her injury and her past. In a preceding dream sequence, when Tár’s bed catches on fire in the middle of the Ucayali River (where Francesca, Krista, and Tár traveled together), “burning” pain is visualized as a side effect of nostalgia. The doctor prescribes nothing for her symptoms, ensuring they will go away on their own, just as nostalgia has no cure but to allow for more time.

Returning to a closer look at the misogamy-misogyny exchange between Tár and Sebastien, the homophones in this scene also underscore Tár’s fear that she is embarrassingly akin to Sebastien. For example, earlier in the film, Tár maligns Sebastien to fellow conductor Eliott Kaplan and calls him (changing Kaplan’s description of him from Mr. Tempo Rubato to Robot-o, the first utterance of “robot” in the film) a robot. As noted, Tár’s repeated use of this insult indicates her anxieties about being a sub-par maestro herself.

During this lunch with Kaplan, Tár also notes Sebastian’s perverse “fetish” to collect such objects as “dead-stock pencils [Herbert] von Karajan holds in photos.”5 Notably, this queer-phobic trope of the “perverse collector” recalls Production Code-era film noirs that align homosexuality with dangerous “abnormailty.” In Otto Preminger’s Laura [1944], the film’s effete villain, Waldo Lydecker–played by Clifton Webb–collects valuable objects and proves his dual misogyny and misogamy when he attempts to murder his female protegee, Laura. When Tár later enters Sebastien’s office, she directs his attention to one of his prized artifacts, distracting him. Stealing a prized pen he often holds and anxiously clicks, Tár references the moment she stills Max’s quaking leg (and proves that she has a knack for making people nervous).

On the one hand, Tár divests Sebastien of his power, his pen, which reminds us of von Karajan’s pencils and looks like a conductor’s baton. (Earlier in the film, as Petra plays “orchestra” with her stuffed animals, Tár tells her “it isn’t a democracy” when she gives all of her animals pencils to serve as batons. With Sebastien, she enacts her right to the role of tyrant not only by taking away the pencil but by doing so without allowing the committee to vote on it.) On the other hand, she draws attention to herself as a fellow “perverse” collector.

Tár collects other things too. After her Gopnik interview, a young woman approaches Tár, and Tár shows more interest in the woman’s red, designer handbag than the woman herself. (Additionally, when Tár first sees Olga in the bathroom at the Berlin Philharmonic, she takes note of her shoes in order to confirm her suspicion that she is one of the people whose shoes can be seen leaving the auditorium after an otherwise concealed performance. In this instant, Tár’s eyes are drawn to the shoes as much as the person wearing them.) Later, returning home to Sharon, Tár totes the same red bag, which Sharon immediately notices as if intuiting Tár’s unfaithful tendency to omit the truth (which Tár does by evading Sharon’s question about where the bag came from).

This uneasy doubling between Sebastien and Tár suggests a misogamist-misogynist link between them. Tár already spotlighted her misogynist tendencies as she wants to end the “quaint” Accordion tradition of only admitting women, as she, in a conversation with Olga, reveals she has no awareness of International Women’s Day, and, as revealed in her Gopnik interview, as she prefers the title maestro over meastra. In this way, Tár codifies herself as masculine and deflects feminine associations with herself, implicitly buying into ideas of female ineptitude and lack.

Furthermore, Tár is the father and cheating husband in her own family. When Petra does not call Tár by her first name, Lydia, Tár is known as “dad.” A cup on Tár’s home office desk, labeled “Dad,” confirms this point. Additionally, Tár refers to herself as Petra’s “father” when she introduces herself to Petra’s school bully. Tár’s repudiation of her femininity and preference for “dad” also reminds us of the absence of Tár’s own father (the film only evidences a mother and brother), opening up a whole other psychoanalytical can of worms.

IX. Rat no Rat

The cycle of repeated marital infidelity is finally broken when Tár fails to secure a romance with Olga. Indeed, the scene in which Tár takes Olga out to lunch repeats and significantly revises the power dynamic between Tár and Max at Julliard. Unlike the nervously twitching student, Olga remains confidently imperturbable. First, Tár misreads Olga by assuming that she, like herself, is vegetarian. Misreading her dietary preferences goes hand in hand with Tár’s misinterpretation of her sexual preference (which we do not know for certain. However, when Olga flirts with a boy at Tár’s book reading, it becomes possible that she prefers men). In the world of the film, too, one’s sexual preference is hardly as shocking as one’s dietary preferences, which, for Olga who orders veal, is as far from vegetarian as one can get.

Because Olga is Russian, Tár also supposes she is a Mstislav Rostropovich fan. Olga prefers Jacqueline du Pré and the Elgar Concerto (which Tár chooses as the companion piece to Mahler to ensure that Olga plays the solo). Although Olga clearly prefers female composers, like Max, she asserts her preference without citing her own social-political identity (despite Tár’s repeated attempts to force identity politics on her, positioning her as vegetarian, lesbian, feminist, Russian, and so on). For this reason, Olga secures Tár’s attraction, admiration, and the reward of a guest solo without a direct transaction, in which a “relationship” is exchanged for professional advancement.

Significantly, Olga knows the concerto from YouTube, not a record. Instead of assuming the role of “robot” for knowing and appreciating music from social media, though, Olga underlines Tár’s robotic, encyclopedic eagerness to know the exact recording and conductor of the Elgar Concerto that Olga listened to. When Tár inquires about the conductor of the piece, Olga responds, “I don’t know who was conducting, but she [Jacqueline du Pré] did something to me.” By taking no interest in the conductor of the piece, Olga divests Tár of the power to make her “feel something”–she translates the emotion for herself, refuting Tár’s belief in the conductor’s primacy as interpreter. In fact, Olga first displaces Tár’s authority when the waiter comes to the table asking for the “maestro’s” order, and Olga speaks first. Tár is now the one who should be offended.

Tár fails to show us her necessity and genius as a conductor, who, as she discusses with Gopnik at the beginning of the film, is more than a “human metronome” (a “Mr. Tempo Robot-o”). Notably, her personal metronome, decorated with the same Shipibo-Conibo design drawn in the novel Krista gives her, haunts her. In one scene, it mysteriously goes off in the night, as if of its own volition, reminding us of the precarious proximity of the metronome to the maestro.

Besides the rhythmic ticking of the metronome, many unintelligible noises irritate Tár throughout the film: the high-pitched noise the refrigerator makes at night, a woman screaming in the park, the medical device alarm, the indescribable sound from the car door as she drives . . . These noises, like music in Bernstein’s view, communicate emotions where language fails. The emotions evoked by these sounds, however, are all ugly, and they imbue the film with dread, fear, and irritation.

By the end of the film, all of the fast-paced dialogue, the overwhelming amount of cultural allusions, the repeated and misheard words, the palindromes and chiasmus, the texts and emails, the scraps of symphonic masterpieces . . . meld together into unintelligible noise, like Tár’s other vacant sounds. Early in the film, as Tár and Andris discuss the peal of someone’s voice that upbraids them, Andris notes, “Schopenhauer measured a man’s intelligence against his sensitivity to noise.” Tár adds that he also threw a woman down a flight of stairs, and Andris counters, “Yes, but it’s unclear if his private or personal failing is at all relevant to his work.”

Recalling Tár and Max’s disagreement about Bach, this debate about personal failing versus the relevance of one’s work repeats throughout the film without resolution. It, too, becomes the noise of the film, offering emotion in place of language (emotions of dismay, frustration, and displeasure). Even in Andris’s statement about Schopenhauer, we are left to ponder the truth: did he find a person more or less intelligent for being sensitive to noise? Considering Tár’s sensitivity, who (no matter what we would like to say about her) is highly intelligent, the film seems to link this sensitivity with the inability to access or make sense of one’s emotions.

Since the film leaves us with unintelligible sounds instead of the truth, we find ourselves offended again. The film’s avant-garde style, as well as its content, offends us by overwhelming us with possible meanings devoid of certainties. All of the film’s embedded “secret messages” (which Tár states while reading from her book about the “secret messages” of music, concurrently watching Olga share such a message with an anonymous boy) lead us to more and more signifiers instead of rewarding us with the ultimate “thing”–argument, ideology, moral, or focus–of the film. Indeed, thinking about the title of Tár’s book–Tár on Tár–we find Tár herself presented in an infinity mirror as she does in the dressing room in the Philippines, appearing again and again, becoming less distinct and knowable with each iteration.

X. If You Hate Tár, Try Corsage

We are eager to be offended by Tár and Tár because offense reinforces our sense of identity and how we politically align ourselves. It is a pleasure to be offended because it is a pleasure to be a member of a community held together through common beliefs and ideas. Additionally, we are eager to take offense in an era of identity politics in which we hold up artistic representation to Max’s very standards–ones that don’t reflect reality but rather a utopic ideal about what humans should look like and how they should behave. Alsop’s offense, too, points to the desire for an uplifting narrative and representation of women, lesbians, and conductors, which Tár gleefully withholds from us.

When I originally arrived at the theater to see Corsage instead of Tár, I gravitated toward a film I knew would make me feel good, even in its tragedy, because of its obvious feminist agenda. Marie Kreutzer’s Corsage (2022), like Tár, dives deep into its main character’s psyche, in this case, the historical figure, Empress Elizabeth of Austria. Unlike Tár, Corsage offers a fantastical re-imagining of Elizabeth’s life to provoke the audience’s empathy for a woman and a 19th-century aristocrat. Indeed, Pablo Larrían’s psychological biopic of Princess Diana in Spencer (2021) offers a similar, sympathetic re-imagining of a much-beloved female royal. Kreutzer and Larrían’s films take great liberty in retelling the lives of their respective historical figures. Yet, the lies these films tell are easier to swallow than the fiction of Tár because we eagerly defend Elizabeth and Diana.

In this way, we’re eager to be offended by Tár because the film neglects reflections of ourselves as we wish to be. Moreover, we are eager to assume that because a film chooses the pitch of the offensive and focuses on the offender, the ideological underpinnings of the film must be unworthy of our attention and dismissed as artless. When we heard “female, lesbian conductor,” we wanted Alsop, not Tár. Yet, as Tár insists to Max, “The narcissism of small differences leads to the most boring conformity.” And what a boring film Tár would be without Tár.

- 1I misuse Roland Barthes critical term. “Punctum,” as Barthes uses it, denotes the “prick” a certain image delivers to viewers who have an intensely private, emotional response to what they view. In fact, Tár experiences a form of “punctum” in the emotional response she has to music, which she tries to translate to others. In my use of punctum, the emotional responses I had to the Julliard scene were more social than individual as I imagined myself being offended on grounds of sex, race and gender that are all socially informed. Speaking of Barthes, this very essay references him and his book S/Z, in which he succumbs to his desire to analyze every word from a short piece of fiction. Similarly, I offer a lengthy reflection of Tár out of the desire to analyze every minute of it.

- 2This phrase is an antimetabole, not a chiasmus.

- 3Significantly, Francesca, who usually wears her hair in neat updos, wears her hair down in the same style and cut as Krista in this scene.

- 4We could also think about how Kubrick, in The Shining, uses the “magical negro” trope with the inclusion of a black clairvoyant as well as in the film’s allusions to the brutal past of Western expansion resulting in the confiscation of Native land and the murder of many Native Americans. In this way, Tár again presents itself as Kubrickian pastiche.

- 5Notably, this queer-phobic trope of the “perverse collector” recalls Production Code-era film noirs that align homosexuality with dangerous “abnormailty.” In Otto Preminger’s Laura [1944], the film’s effete villain, Waldo Lydecker–played by Clifton Webb–collects valuable objects and proves his dual misogyny and misogamy when he attempts to murder his female protegee, Laura.

Leave a Reply