Viewing Breakthroughs: A Celebration of RedLine at 15 with Artist, Alicia Ordal

Alicia Ordal stood in Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art gift shop, waiting for me in white and mauve checkered pants. She coincidentally fit in with the merchandise, which caters to a young audience with 1990s nostalgia (regardless of how conscious they were during the 90s). The MCA’s marketing and special programs target teens and align well with the currentness of its content. Indeed, searching for one’s place in the world becomes a lifelong endeavor that contemporary artists document through innovations in visual language.

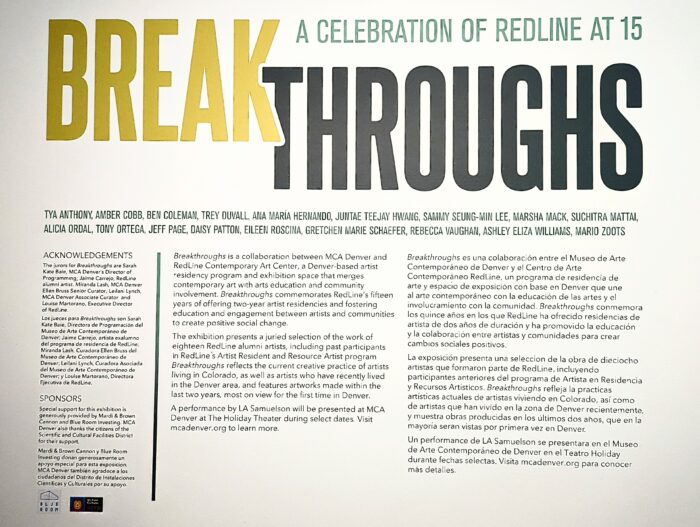

The MCA’s current exhibition, Breakthroughs: A Celebration of RedLine at 15, showcases work from RedLine residency alums who assert their rightful place in Colorado’s contemporary art scene. I asked Ordal, one of the eighteen featured artists, to guide me through the exhibition. Ordal received a two-year residency when Laura Merage and The David & Laura Merage Foundation launched the nonprofit art center in 2008. In the historically black Five Points neighborhood, RedLine boasts an ample gallery space surrounded by open artist studios. Although Ordal currently rents a studio at TANK, created by former RedLine artists to provide their cohorts with affordable studios, her previously-occupied studio at RedLine hosts other emerging regional artists.

Artists including Sammy Seung-Min Lee, Marsha Mack, Suchitra Mattai, and Tony Ortega demonstrate how personal, historical, and mythological symbologies articulate identities touched by immigration and cultural hybridity. Others, including Daisy Patton, Eileen Roscina, Juntae Teejay Hwang, and Rebecca Vaughan, grapple with the confounding mixture of joy and anxiety that arise from family events and, to use Patton’s critical phrasing, “re-contextualize” the past with the present.

Right, Suchitra Mattai, “Held Still (in silent echo),” 2021

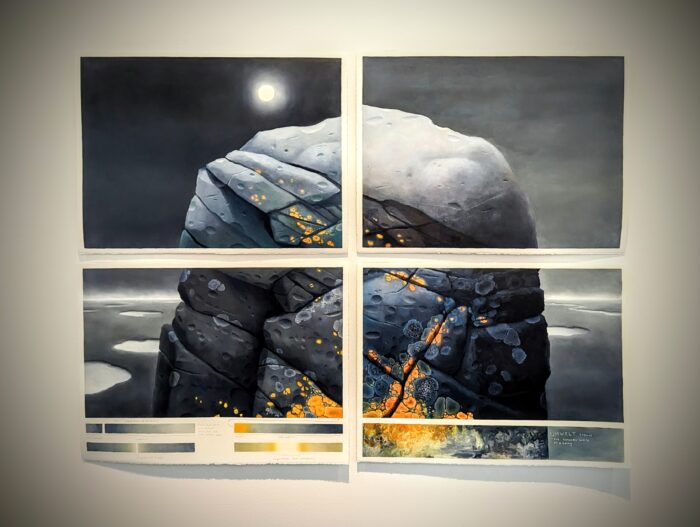

Many pieces in the show underscore the artists’ desires to overcome the constraints of verbal language by exploring alternative ways to speak with the environment around them. These artists include Gretchen Marie Schaefer, Jeff Page, and Ashley Eliza Williams.

In addition to this permeating theme of communication, Ben Coleman and Trey Duvall demonstrate an interest in everyday objects, absurdity, and sound. The remaining artists, Amber Cobb, Mario Zoots, and Tya Anthony, consider language or communication alongside abstraction, asking more formal questions without erasing their backstories.

We purposefully viewed Ordal’s piece last, first coming into view from the ground-floor balcony, looking down into the basement. “Originally, I wanted to play with the architecture of this building, which I love,” Ordal looked around her to admire the sleekly modern space created by Adjaye Associates in 2007. “But then I decided to create just one piece and put it in the basement.”

Consequently, Ordal’s change of heart made room for Ana María Hernando’s “tulle paintings” to interact with the space.

Left, one of Hernando’s “tulle paintings.”

“Let’s get a picture of you,” I directed Ordal, like a proud mom, next to her piece. “It’s OK,” I said, addressing the young gallery attendant, “She made this piece. So, she can touch it.”

“I figured from the conversation,” the attendant responded, turning her eyes to Ordal. “I really love the material you used. I didn’t realize at first that it was carpet padding. Did you mean to use it to look like marble?”

Ordal’s sculpture, a Z-shaped octagon entitled “Birdsmouth,” looked, to my eye, as if made from granite slabs. Ordal recounted how she first saw the material when a maintenance person left it in the hallway of her apartment building. “He left it there for a couple of weeks,” Ordal stated. “But the day I finally came to take it, he showed up for it.”

The man returned to give Ordal the leftover material, and she went to the home improvement store for more. As exemplified in her use of this padding, Ordal conscientiously chooses materials. Often these materials are upcycled products, such as toilet paper rolls, upholstery foam, and rope.

When I asked her about the piece’s title, she informed me that “birdsmouth” is a woodworking joint, which she originally planned to incorporate. “I had to give the MCA a title before I made the piece,” Ordal explained. “I’m OK with the title referencing something that’s not even there, though.” Ordal’s birdsmouth-less sculpture, therefore, responds to “the [ubiquitous] boxy Denver loft” by referencing a not-even-there habitat in the city.

For several years now, Ordal has occupied a rare fixed-rent basement apartment in the Denver Highlands neighborhood. (Note how both Ordal and her sculpture inhabit the basement of a building.) Indeed, this historically Latino and low-income neighborhood exemplifies recent, widespread gentrification in Denver.

Once a diverse, residential area, the Highlands now teems with expensive loft buildings, high-end restaurants, and an assortment of gyms, spas, and boutiques that cater to a growing number of white, upper-middle-class young professionals. Many early 20th-century Victorian and mid-century modern homes in the neighborhood have been demolished and rebuilt as monstrous mixed-material hybrids of glass, wood, metal, and stone.

Echoing the architecture around Ordal, “Birdsmouth” incorporates three plastic “windows” in the top left corner of the octagon, covered by a construction-cone-orange tree branch. A wooden ladder leans against the bottom right quadrant. Caught in a dark, polluted cloud that shades the underbelly of the piece, the ladder proposes that we climb out of the muck to access Ordal’s dwelling. Moreover, the name “Birdsmouth” suggests an elevated nest. Drawing from and refuting the world around her, these elements underscore Ordal’s desire to inhabit an imagined space still rooted in the reality of a city she calls home.

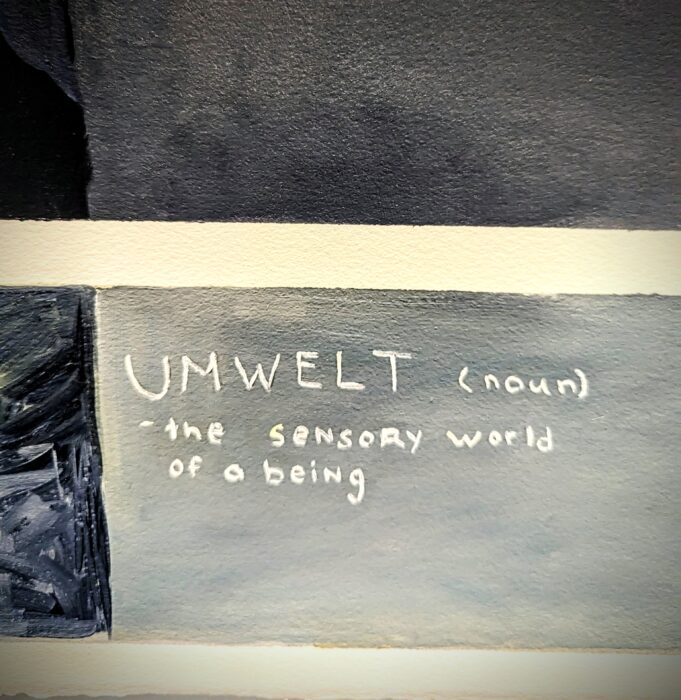

In other words, Ordal’s visual reverie holds on to utopic, inclusive futurity by providing an alternative to dystopic, segregating present-day developments. Earlier that day, Ordal showed me a blueprint for the facade of a different dream home generated on her computer. This home also repudiates the uninteresting square loft with its polygon shape. Composed of red brick on one side and yellow brick on the other, the house features a large porthole window tinted purple, a dark green door decorated with a vertical column of transparent glass bricks, and an outdoor rooftop patio. Designing structures satisfying her standards, Ordal passively resists immersion in a world of haphazard design that she lacks the authority to alter.

“Birdsmouth” relates to a handful of other works in the exhibit that manufacture fantasy environments as expressions of existential displacement. Moreover, these constructions express desires to belong somewhere and a find home. For instance, Sammy Seung-Min Lee’s installation utilizes suitcases to invoke the estrangement that immigrants feel after establishing themselves in another country. Underneath these suitcases, Lee laid a block of reflective silver vinyl. The parameters of this mirror flooring comply with Colorado state law, which defines 100 square feet as the minimum amount of space suitable for an “adequate shelter.” Although Lee’s work draws from her own experience as an immigrant from South Korea, her installation also brings to mind Denver’s pervasive homeless population.

In contrast to Lee’s gloomy installation, Marsha Mack translates her vibrant private paradise through a “visual vocabulary of personal symbols.” Such symbols include Pocky boxes, a Japanese candy, alluding to her nostalgia for visiting Asian supermarkets as a half-Vietnamese child. Backdrops of lush jungle waterfalls hang behind her ceramic sculptures of delicate, feminine hands in balletic mudras, fruit rendered as jewelry, a pair of black swans in a clamshell. . . pieces that would be at home on a vanity set in a girly bedroom. Indeed, Mack takes up an entire room in the museum, adding to the work’s voyeuristic pleasure by granting us exclusive access to someone else’s Eden.

In this continuum, “Birdsmouth” lies between Lee’s dreary display of transience and alienation and Mack’s baroque fantasy. Moreover, while Ordal’s longing for home (a place of solace, ample space, security, and acceptance) does not arise from experiences of being biracial or an immigrant, her attention to it highlights its universal elusiveness. Denver, too, seems to grow more inhospitable for artists who cannot afford to live and work here, for immigrants who feel exoticized, for women who feel unsafe, for people of color brutalized by the police, for families torn apart by gun violence . . . For one reason or another, this city pushes everyone out.

These ideas doggedly pursued us as we left the MCA for RedLine in a hotspot of homeless encampments. Its current exhibition, a retrospective on Denver-based photographer Mark Sink, opened on April 1st, 2023. Coming to a wall of “wetplates,” photographs made by pouring collodion on a glass or tin plate before adding silver nitrate, we recognized our friends from the Denver art scene. “Here’s you!” I exclaimed in front of Ordal’s picture. “And here’s you again!” How fitting that Ordal appears simultaneously in RedLine and the RedLine show at the MCA, among her friends, where she belongs, in more-than-adequate spaces that support artists in a tough city. She may not feel entirely at home in Denver, but here is proof that she is welcomed and appreciated.

Breakthroughs: A Celebration of RedLine at 15 opened on February 24, 2023, and is on display until May 28, 2023. Curated by Miranda Lash and Leilani Lynch, the exhibiting artists include Tya Anthony, Amber Cobb, Ben Coleman, Trey Duvall, Ana María Hernando, Juntae Teejay Hwang, Sammy Seung-Min Lee, Marsha Mack, Suchitra Mattai, Alicia Ordal, Tony Ortega, Jeff Page, Daisy Patton, Eileen Roscina, Gretchen Marie Schaefer, Rebecca Vaughan, Ashley Eliza Williams, and Mario Zoots.

Leave a Reply