A Portrait in Words and Photographs of My Uncle Mark Bird, a Vietnam War Veteran

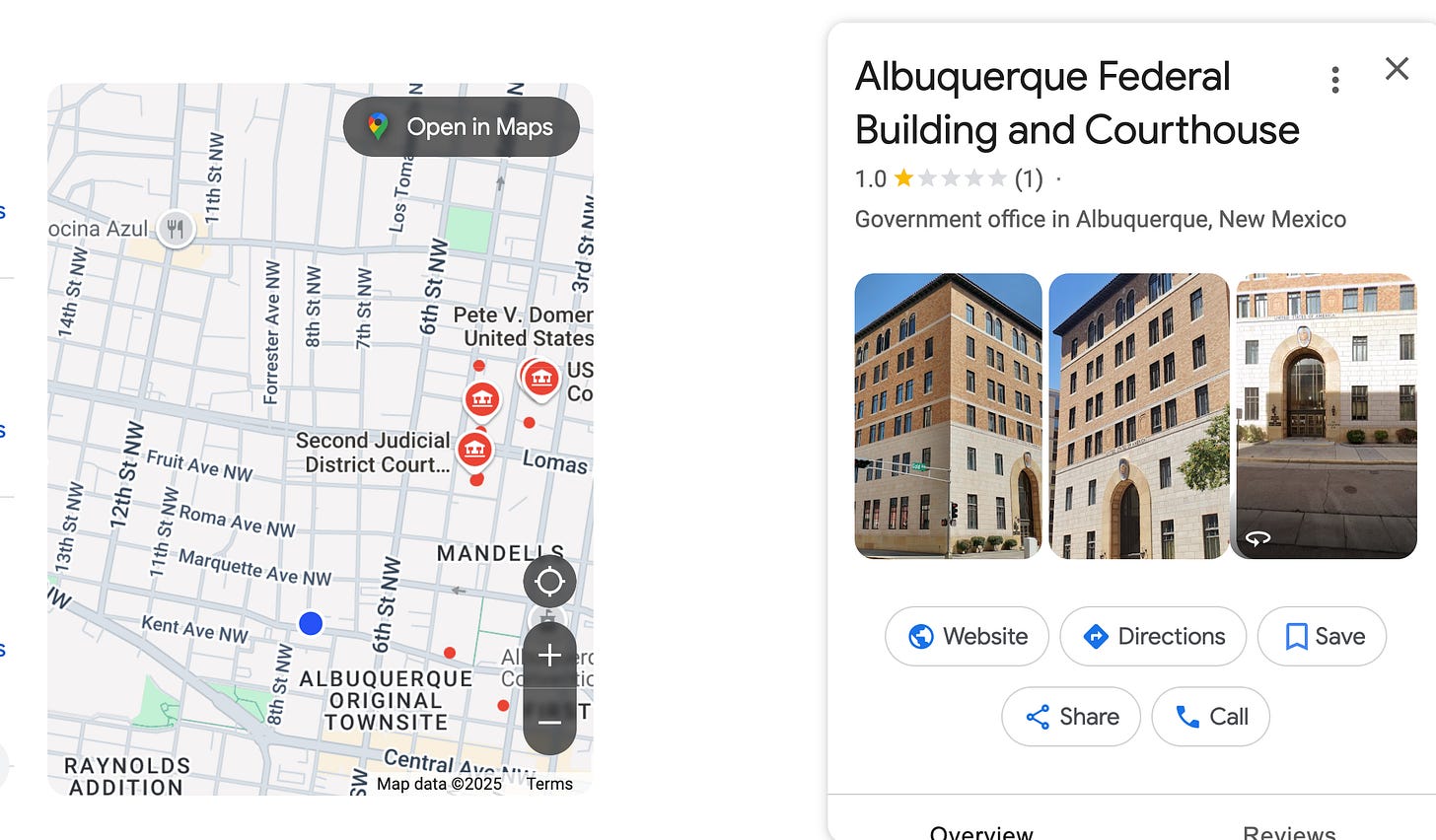

On Veteran’s Day, I took my uncle, a Vietnam War veteran, and his partner, a Vietnam War protestor, to coffee in downtown Albuquerque. Trump had just been elected for a second presidential term, and our conversation waxed political, full of anxiety and hope. A few days earlier, I had asked my uncle to be the subject of a photography project in which I thought about what it looked like to have a life after being drafted into the Vietnam War.

Following the coffee, we walked a few blocks to The Federal Building on Gold Street, the site he remembers reporting to as a recruit in the 1960s or ’70s (his exact timeline eludes me). I snapped a few pictures while he milled around the attractive brick structure. Then, when I got home, I realized I had forgotten to put a memory card in my camera. Those pictures are now lost in everything but my memory of taking them.

My uncle is notoriously and understandably reticent on the subject of the war. The fact that he had been involuntarily sent to teach English in a place where he also undoubtedly watched people die and get tortured and raped never occurred to me as I grew up. I thought of him as my uncle—the bachelor who lived in a hovel full of yard-sale trinkets. Occasionally, while my family lived in Wyoming, he would show up at our doorstep, staying for weeks in order to build us an enclosed porch or to accompany us on a road trip to Yellowstone.

Of course, I know now that he will probably never feel like an innocent witness to the horrors that transpired in Vietnam.

We developed a special connection over time, finding ourselves ideologically aligned as well as intellectually curious about the same books, films, and art. We wrote each other irregular letters. On one of his visits, he gave me a weathered copy of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. Perhaps on the same visit, we rented The Scent of Green Papaya from the local Blockbuster, a film I found painfully slow and boring as a teenager. I didn’t then make the connection that it was a Vietnamese film about the pre-war life of a young girl who does housework in Saigon.

War didn’t mean much to me in the 1990s—it was way over my head and before my time. It happened in the past for complicated and unavoidable reasons. Additionally, it was the stuff of classic literature and earnest Hollywood features like Forest Gump, which I can still hear my father weeping through when we saw it in the theater. I was nine years old–old enough to learn about PG-13 depictions of the Vietnam War, transformed into a romantic comedy.

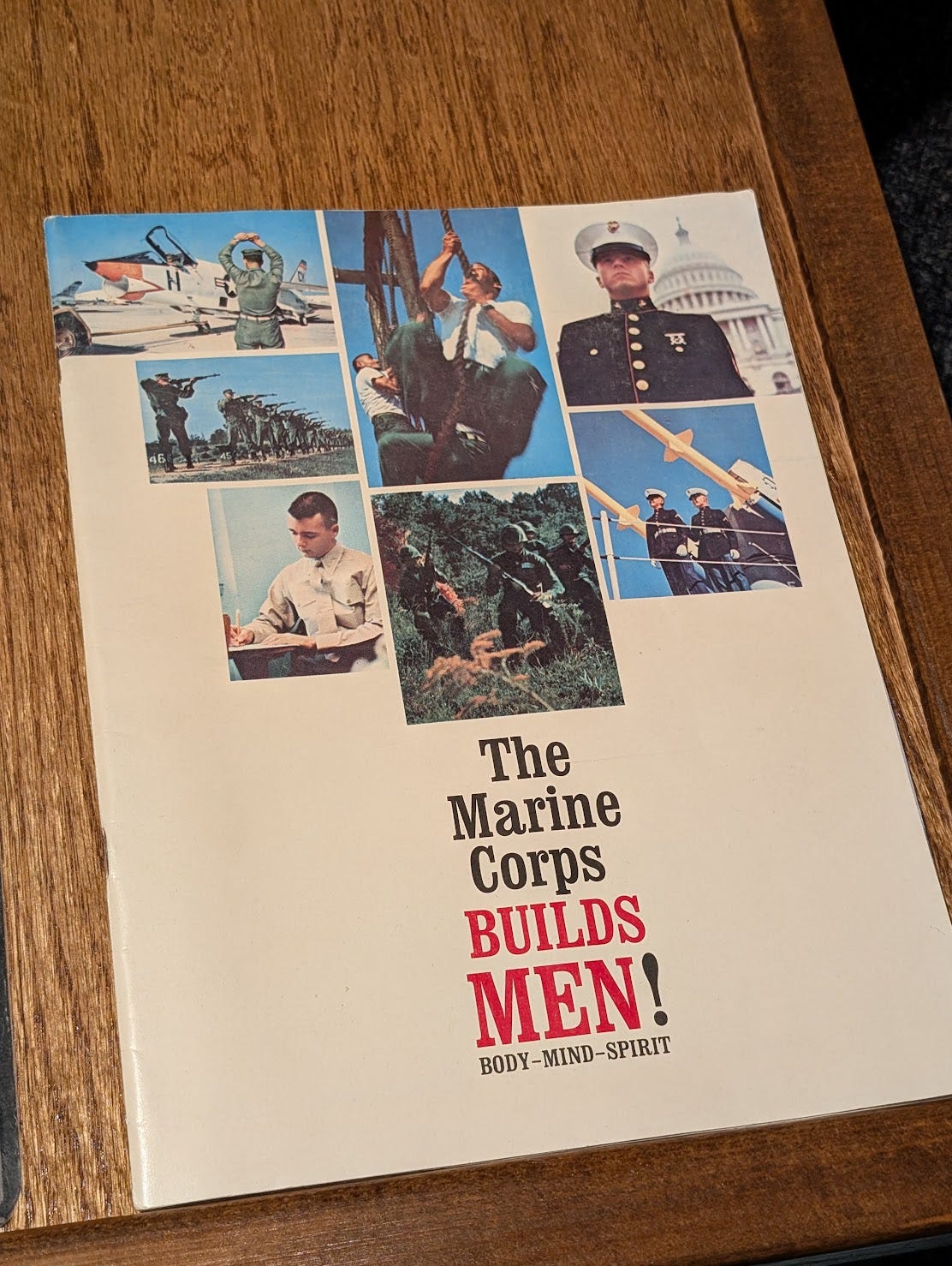

The narrative about war is endlessly malleable, often pleasurably aestheticized, and so capable of rendering the grotesque and macabre inextricable from beauty. A classic and engaging tale, war is the avenue by which good conquers evil. It ennobles us as individuals, “builds men,” and produces prideful nations. Proudest of all are the victors, who subsequently rise as members of a powerful global elite.

Not to out myself as a stereotypical millennial, but the events of 9/11 certainly brought the idea of war—and the US as a war-mongering nation—to the forefront of my mind. Initially, I didn’t know what to think as I watched the Twin Towers fall on a bulky television in my high school world history class. The event and the ensuing Iraq War felt like an anachronism. How could we find another war necessary after waging so many excessive, unsuccessful, and unpopular ones in the past?

Needless to say, the only outcome of this conflict was the death of tens of thousands of Iraqis and Americans. The survivors who returned home, traumatized and maimed, found it hard to integrate back into society. Now, most of us agree the war was needless. There were never any weapons of mass destruction, and the whole enterprise seemed to be a way to dangerously extend executive power and enrich Halliburton–the oil and gas company in which Dick Cheney was heavily invested.1

In the background of this international drama, my uncle was toiling on a small plot of land in Moriarty, New Mexico. Like many Vietnam veterans, he didn’t come back feeling transformed into a hero. He felt “changed”—as many veterans comment about going through war—but the ways in which the war changed him will forever dodge articulation. Men like him were also met with the vitriol of anti-war protestors who blamed them for fulfilling a fate many of them regretted or were unwillingly conscripted into.2 As a result, some chose to retreat into remote hermitages. I’m sure others took their own lives, either quickly or through the slow death of drug and alcohol addiction.

After several years of listlessly meandering through South America and the East Coast, my uncle settled in his own hermitage near his parents in Moriarty, a rural town east of Albuquerque. He had hoped that one day Moriarty might grow and develop. It never did.

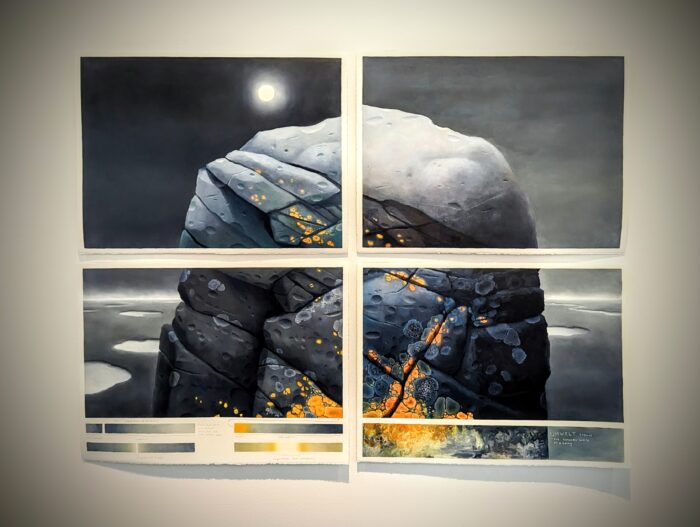

As a construction worker who specialized in plaster and adobe, his place in Moriarty became the lab where he tried out different techniques. Soon, elements of prefab houses melded into adobe edifices with Earthship-like tire insulation and walls punctured with glass bottles. Colorful tiles decorated sporadically chosen wall spaces. Various genres of antiques spilled out of each room and into the yard, dissolving the boundary between outside and inside. Cars, trucks, trailers, RVs, and industrial machinery choked his lawn.

If you live in New Mexico, you see many properties that resemble my uncle’s. My family used to point out any lot with an obscene collection of automobiles and say, “There’s an Uncle Mark house.” But, of course, we were only pointing out how unoriginal his property was in comparison to many others.

Perhaps this dispersed community of amateur house-builders and refuse collectors shared similar dreams of self-sovereignty, which I am sure infected my uncle. Indeed, the Earthship community in Taos flourished when he returned to the US, fueling the widespread ambition for a self-sufficient, off-grid life.

Recently, I’ve been pondering if the properties we singled out as “Uncle Mark houses” also belong to veterans. At any rate, they are coded as spaces for those on the fringe of society.

At some point in the 2010s, the city threatened to serve my uncle a hefty fine if he did not clean up his property. They were enforcing a seemingly arbitrary standard of how much open-air junk the county deemed sightly. He was understandably outraged—especially because his living conditions were in line with the rest of the neighborhood—and the mandate sunk him into a depression.

I still recall the anger in his eyes during this period. He had done his part as a citizen of this country, more than most of us. Why couldn’t the government let him live the life they had already tried to take away?

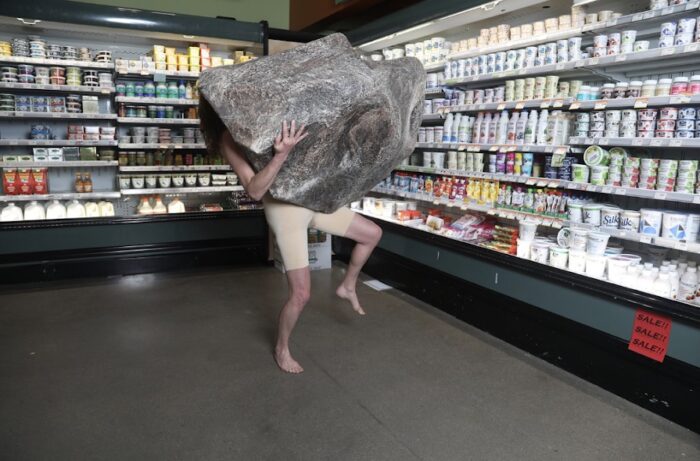

Although I don’t remember the details, he went to court and was eventually made to comply. He cleaned things up, selling many of the rusty treasures littering his yard. After he met his partner, he continued to live on and off in Moriarty until he took up a full-time residence with her in Albuquerque. The site of his life’s work—which I have always considered a sprawling art installation piece, meditating on temporality and a war-changed psyche—was left behind, remaining unfinished.

Before Thanksgiving, we drove to Moriarty with my photography gear and his dog, Tako, in the back seat. On the drive, I wanted to prod my uncle with questions about the war. However, I couldn’t find the right questions. Or maybe I lost my nerve.

In September, he had undergone open heart surgery to replace a heart valve, and our conversation veered in this direction. He told me the world appeared different to him now, but he couldn’t explain how. Recovering well after a successful surgery, he nevertheless felt that he had touched death. As a result, he couldn’t fully return to this life.

Whatever existential crises, if any, the Vietnam War had awakened in him decades ago, they have become less colorful and important. The prominent battle he now fights deals with advancing age.

Physically, he still appears strong and handsome. A few years ago, he lost sight in one eye, transforming his brown iris into a milky blue blob. “I’m a husky now,” he had told me when I first saw him after this incident. His dead eye, along with the new scar tracking vertically down his sternum, only enhances his physical appeal.

I can’t help but acknowledge that the codification of his handsomeness is directly linked to the icon of the warrior-hero—the man who, like the knightly Marine from “The Few and the Proud” ads, bears the sexy scars of an epic battle. Of course, my uncle’s scars were not received in direct combat. Yet, they strike me as the byproducts of exposure to the physical and mental catastrophe of war.

I wanted to capture all of these ideas in my portraits of him: how his enduring strength, paired with the breaking down of his aging body, remains interlocked with his past and who he is constantly becoming as a person. To me, his scars have finally externalized the indelible marks of the events that forever altered him.

The icy wind was snapping at us as we approached the front door of one of the structures that stood on his property. We hadn’t dressed for such unseasonable weather. Searching his pockets, my uncle realized that he had forgotten his keys, limiting us to unsheltered outdoor shots.

I hastily tried to keep up with him as he wandered his estate. He strode quickly, endeavoring to stay warm while surveying how fast the decrepitude had blanketed his unmaintained property. The rampant deterioration cast a visible melancholy over him.

As an amateur, I fumbled to set my camera to the right settings for good exposure. After much fussing, I squinted into the viewfinder to find him unsure how to pose. Since I was hesitant to direct him, I photographed him in his discomfort.

Even under more favorable weather conditions, I would have been testing my uncle’s patience with how long it took me to adjust my tripod and flash. Just as the coveted golden hour was beginning to emerge, he rubbed his numb hands together, cursed, and pronounced that he was done. I slowly followed him back to the car, struggling to get a final shot of a plastic Virgin Mary statue blessing shards of China on a rotting plank of wood.

“We will have to come back in the spring,” I told him as I drove us west.

***

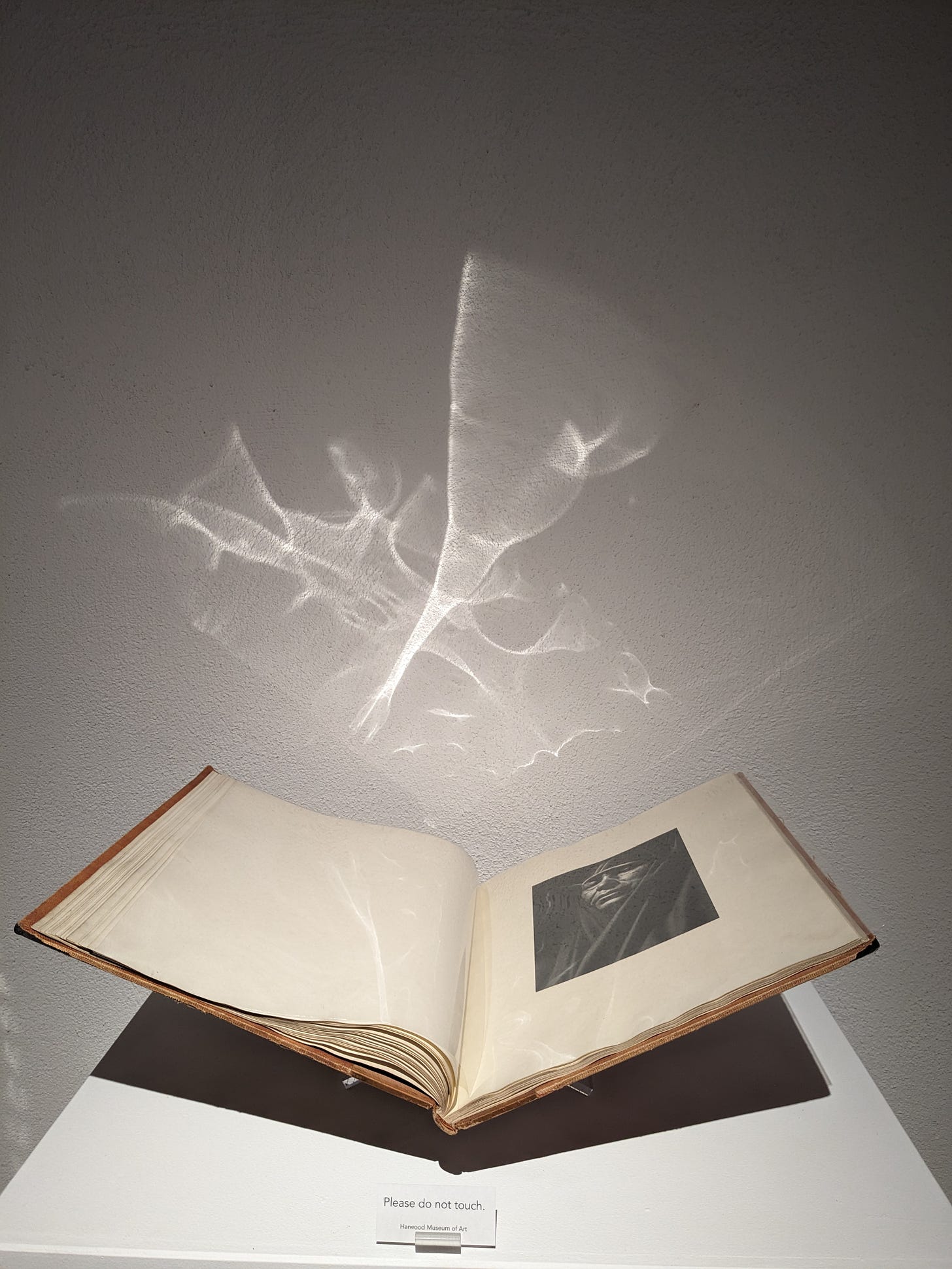

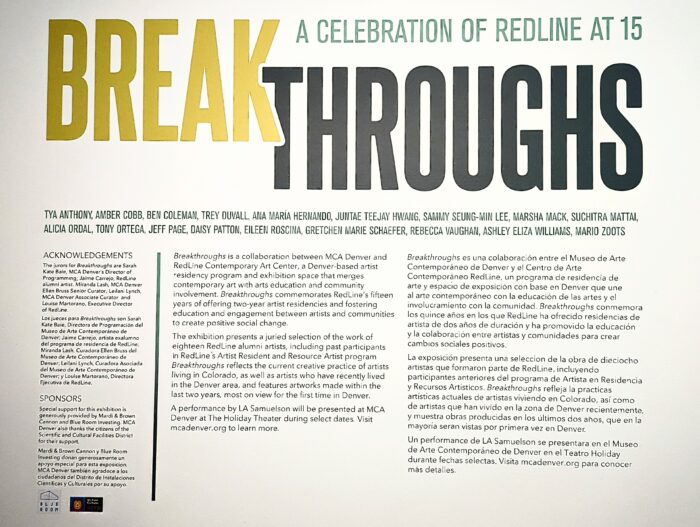

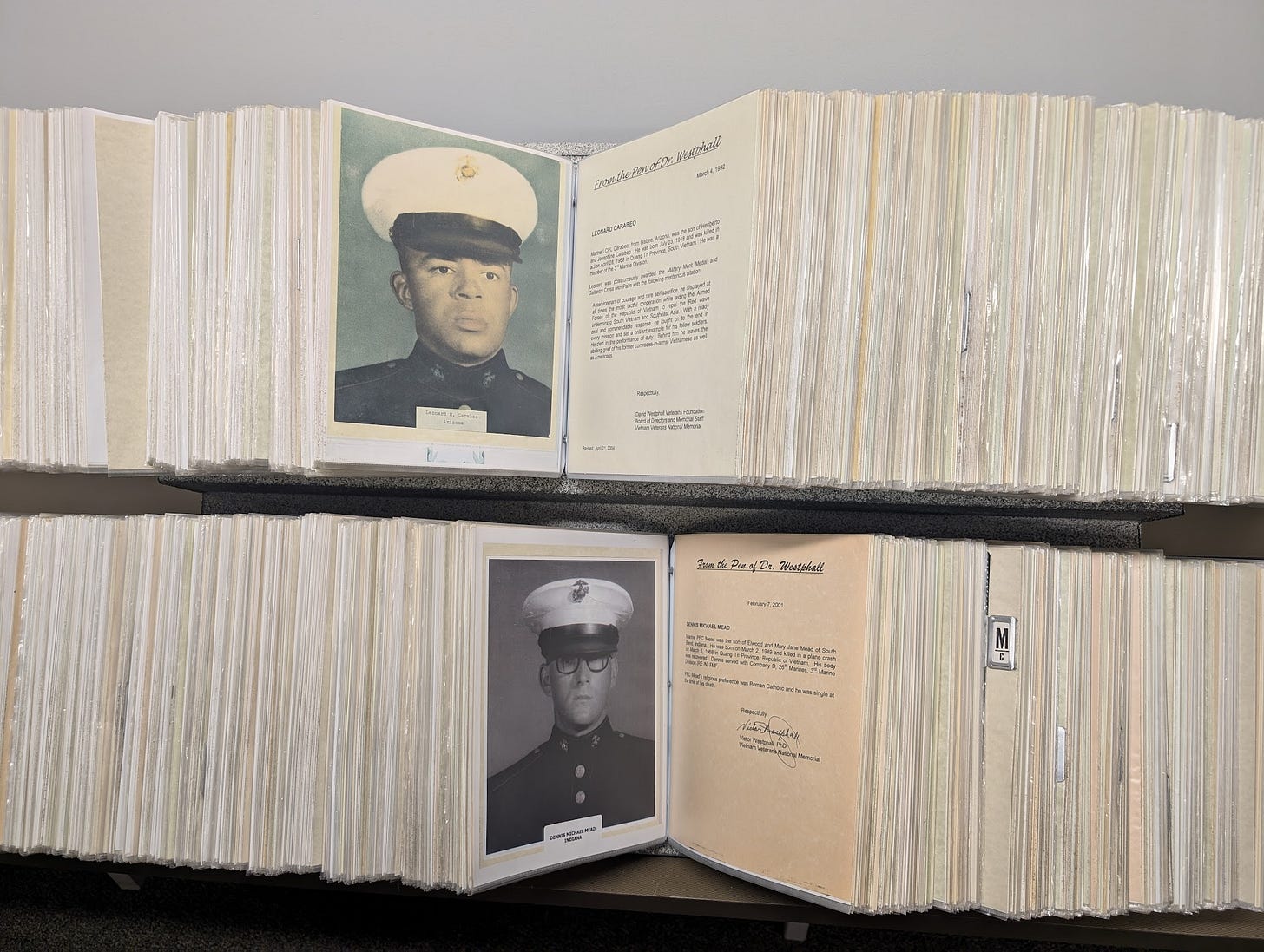

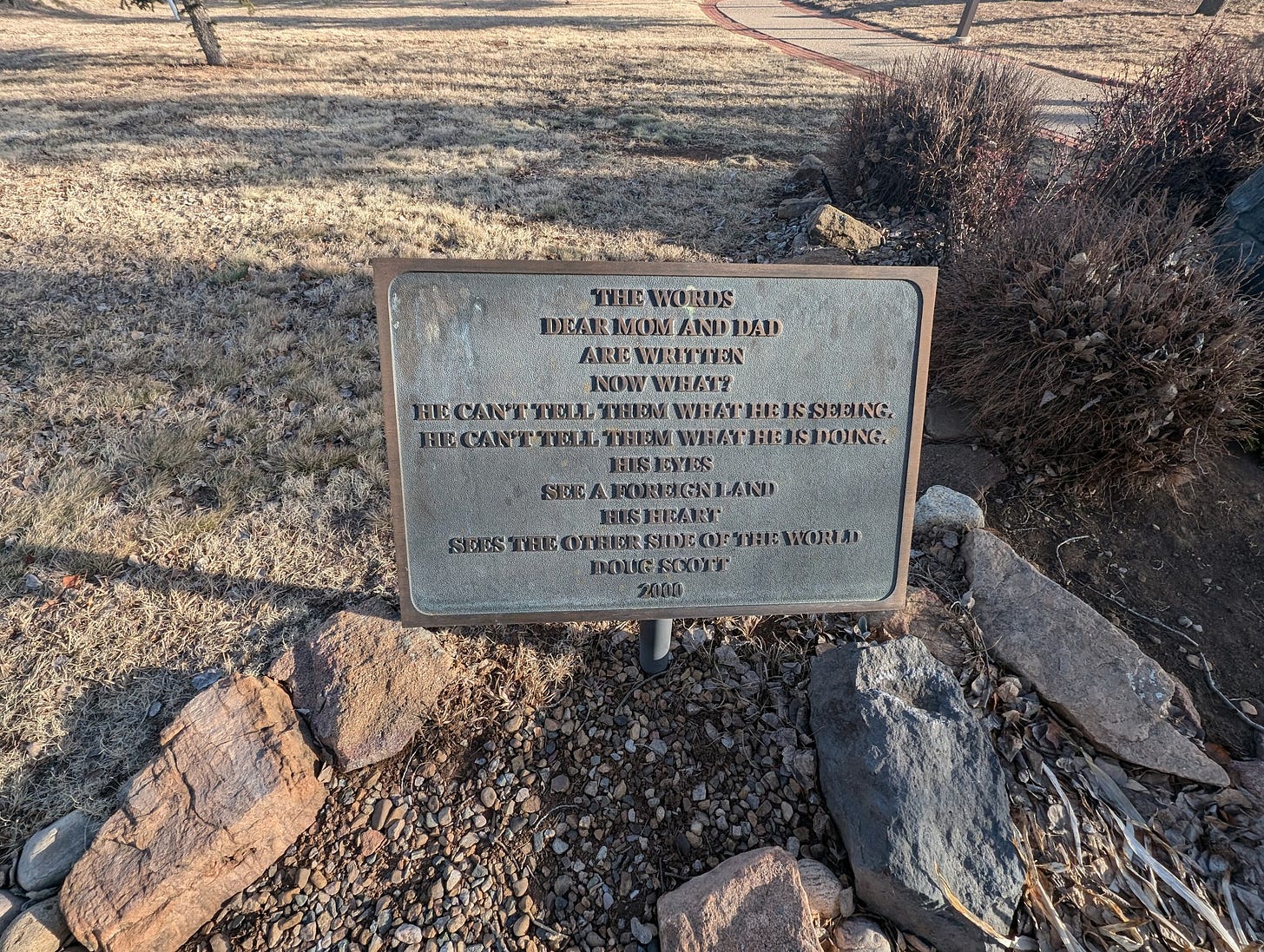

After the New Year, I found myself in Angel Fire, NM, searching for snow in a snowless ski town. Instead, I found a Brutalist chapel at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Built with the life insurance money Jeanne and Victor Westphall collected from the death of their son, David, the couple wanted to honor his untimely death in Con Thien, Vietnam, in 1968, with a public memorial site designed by Victor.

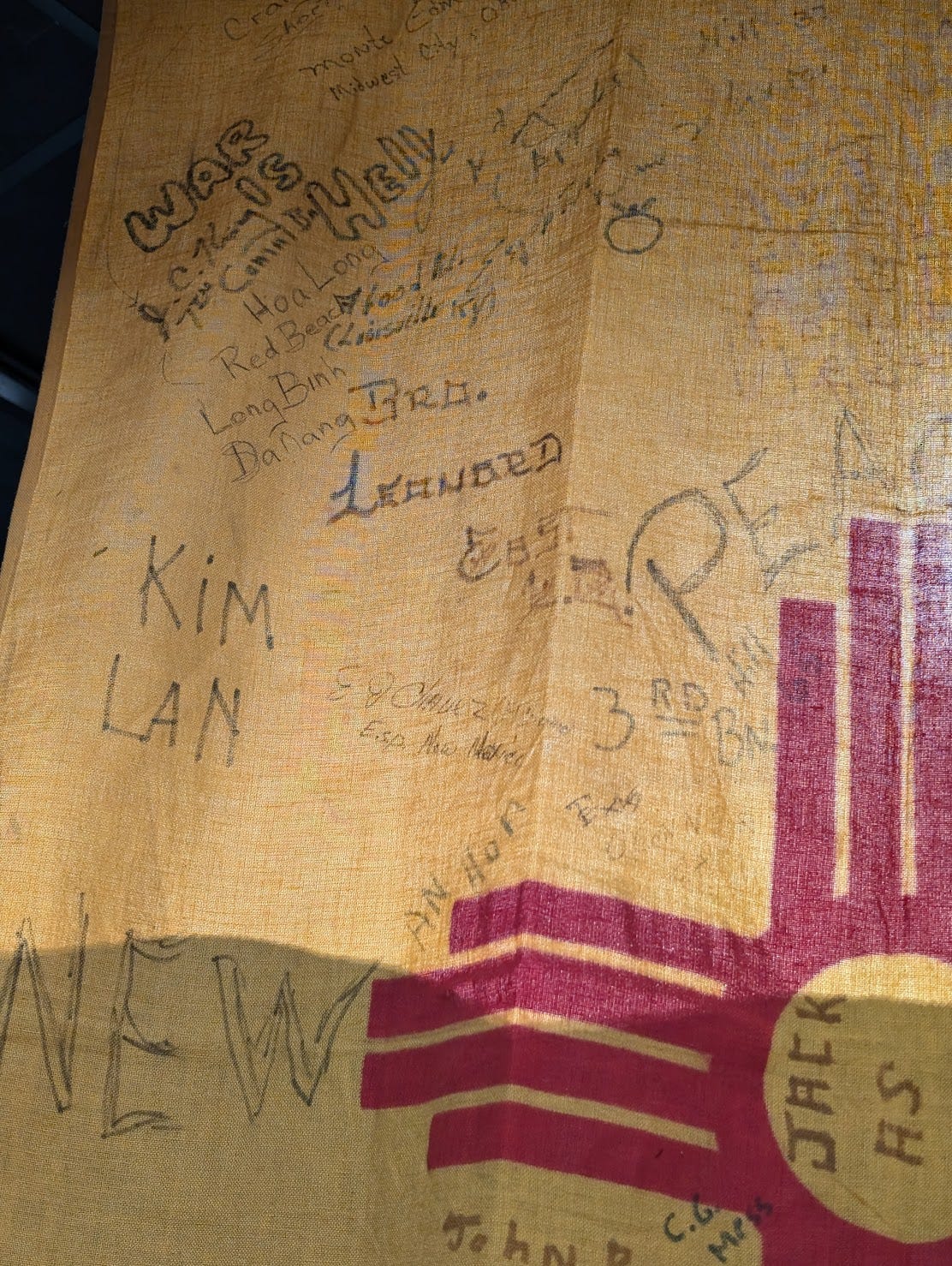

In 2017, the Department of Veterans Services built a museum and gift shop next to the chapel. When I first walked into the museum, I noticed a display case with Vietnamese items, including old stamps, currency, cigarettes, phrasebooks, and dolls. It felt like a preserved 1960s travel agent’s desk. I could hear the slogan: “Come to beautiful Vietnam and experience its timeless Oriental charm!”

This display, so sanitized of overt violence, stung my eyes with tears, which prompted me to spot a nearby box of tissues. I soon realized that these boxes were carefully placed all over the exhibit, beckoning pity.

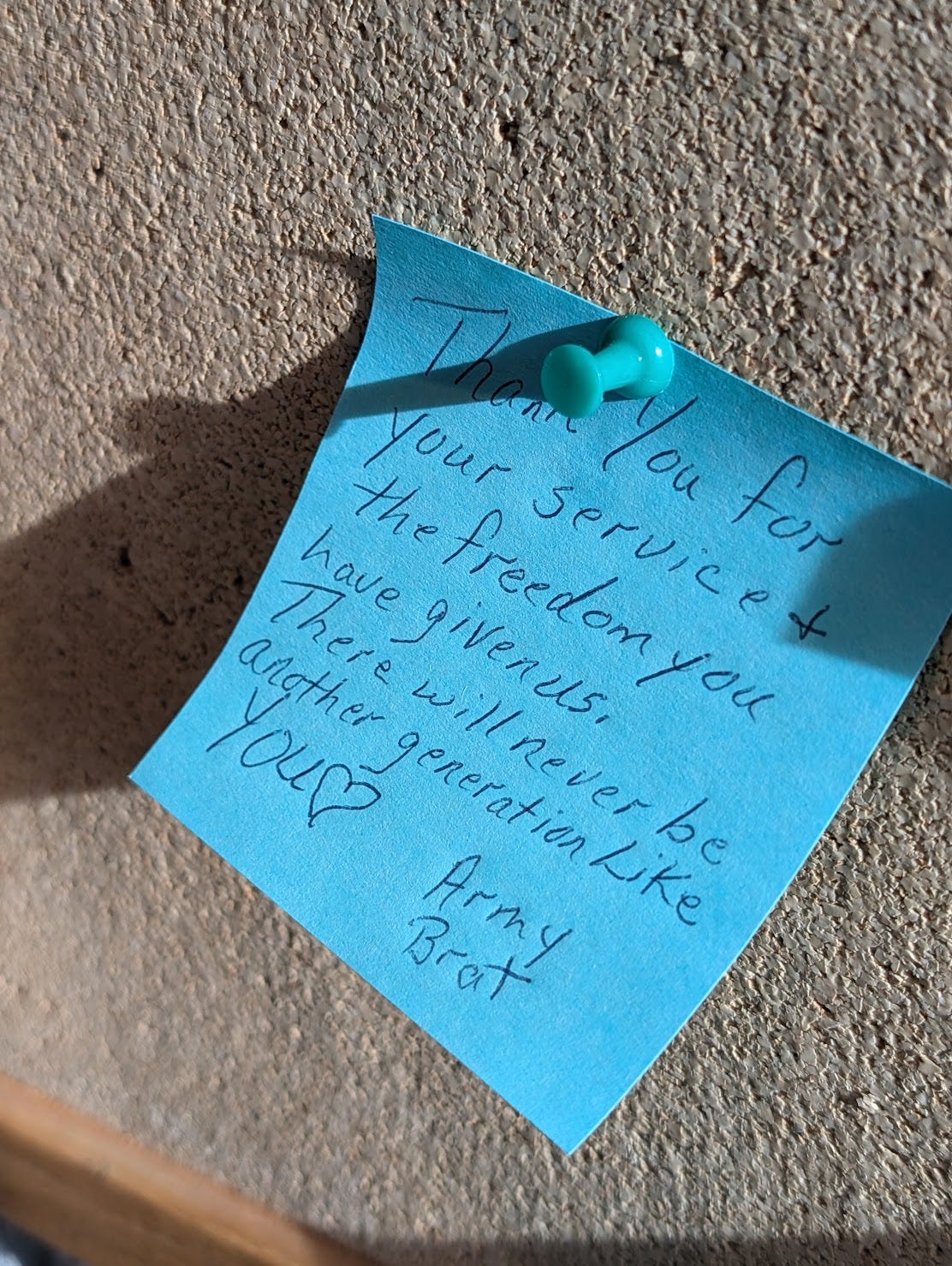

While I knew what was upsetting me in this space, I wasn’t sure what the curator of the tissue boxes had hoped I would feel. The pointed tissue offerings communicated to me that we were all expected to feel the same way about this history. We were all expected to cheer for the same side, too, and I doubted the tissues were inviting us to grieve the loss of Vietnamese lives.

I held back my tears, not wanting anyone to think they were shed for the men and women who fought for my American freedom. My tears were not grateful. If anything, they expressed how overwhelmed I felt pondering the futility of war—its senseless ruining and taking of lives—and our powerlessness to stop it. If the tissues were expressly provided for that purpose, then perhaps I would have let my tears flow freely.

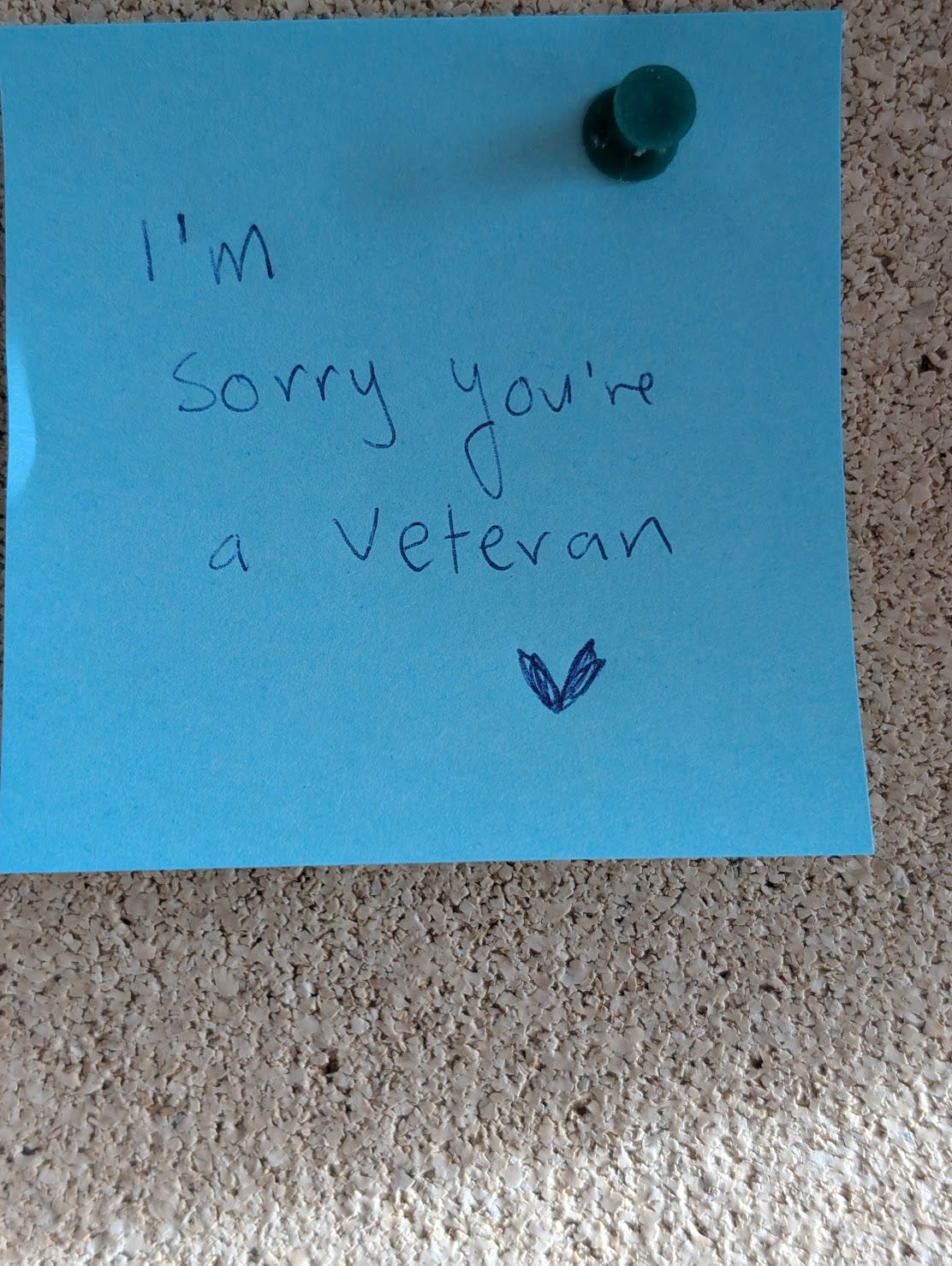

On the way out, a board of post-it notes displayed the handwritten messages of visitors, thanking the veterans for their service. I took a pen and scribbled the message my uncle, his partner, and I decided was the best thing to say to a veteran on the Veterans Day we recently shared together: “I’m sorry you’re a veteran.”

Find a list of all of my published works on my website here.

Recently, I found out that my uncle’s birth on May 7, 1948, preceded the day Israel became a nation by a week. As I pen these anti-war reflections, it would be remiss of me not to underline this coincidental connection while acknowledging one of the deadliest genocides in my lifetime, currently happening in Palestine. I’ve shared some of my thoughts about Israel and Palestine more extensively here and here.

Not to overlook the African, Hispanic, and Indigenous Americans who thought that joining the military would prove their rightful status as full and valued US citizens.

Find my Substack and subscribe here.